The World’s Most Southerly Periodical

by Anne Fadiman

On February 8, 1902, the steam-powered barque Discovery anchored in McMurdo Sound, carrying Robert Falcon Scott’s first Antarctic expedition. Its cargo included guns, axes, saws, sledges, skis, compasses, chronometers, barometers, thermometers, microscopes, telescopes, magnetographs, theodolites, fireworks for signaling, explosives for blasting through ice, a windmill to generate electricity, a balloon for aerial surveys, a set of magic tricks, a collection of theatrical costumes, a piano, a harmonium, 36 cases of sherry, 5,000 pounds of marmalade, and more than 1,500 books, 48 of them by Sir Walter Scott. The Discovery also carried a single typewriter, a Remington No. 7, on which Ernest Shackleton, the Third Lieutenant in Charge of Holds, Stores, Provisions and Deep Sea Water Analysis, would perform an additional and perhaps even more vital duty, as the founding editor of Antarctica’s only magazine, the South Polar Times.

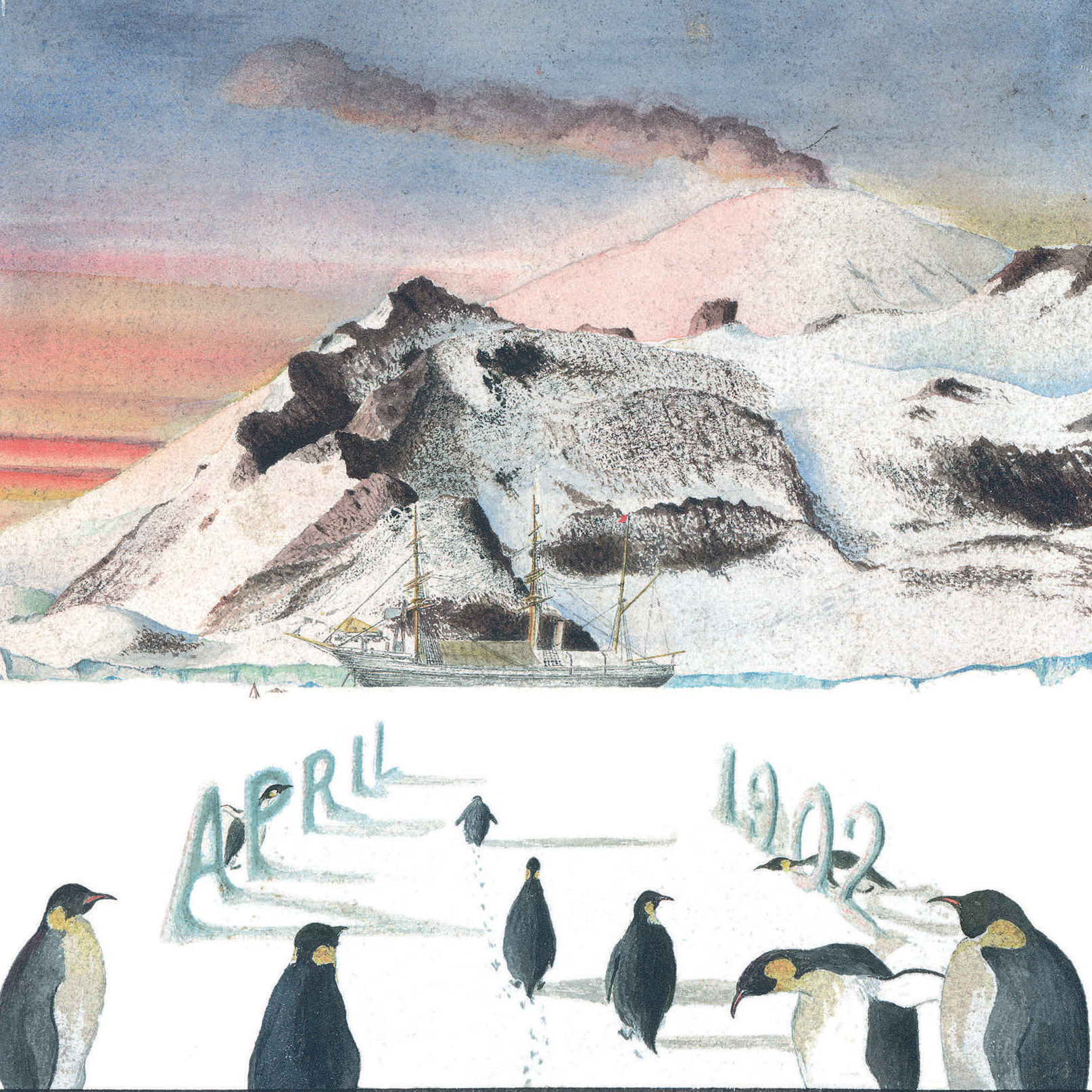

Michael Barne, South Polar Times, April 1902, cover. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG). The cover of the first issue shows Discovery frozen into the pack ice beneath Mount Erebus.

The South Polar Times is proof of something all editors know and all publishers deny: that the value of a periodical cannot be judged by the size of its circulation. There was only one copy of each of its twelve issues, to be shared (depending on the year) by between thirteen and forty-seven readers. It would come out monthly, but only in winter. The Antarctic sun set in April and did not rise again till August. Previous expeditions had learned that four months of darkness could make men despondent and mutinous. “I can think of nothing more disheartening, more destructive to human ambition, than this dense, unbroken blackness of the long polar night,” wrote the ship’s surgeon on the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–98, during which one man had died, two had gone insane, one had attempted to walk home to Belgium, and many had watched their hair turn gray. In the winter of 1899, a member of the British Southern Cross expedition to Antarctica wrote that “a gloom would envelop the mind in as thick a canopy as a London fog.”

Edward Wilson, “Snowdrops & Violets,” South Polar Times, April 1902, p. 8. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Scott had no intention of permitting any such fog to envelop his own expedition, during which the Discovery spent two winters in Antarctica, frozen into the ice while awaiting the sledging seasons, when much of the scientific work would be undertaken and an attempt made on the South Pole. His antidotes were books, music, games, debates, and amateur theatricals (with some of the men in drag and others in false mustaches), along with strict social boundaries between the seamen, who dined on the mess deck, and the officers and scientists, who dined in a wood-paneled wardroom, on a table set with linen napery and china, after saying grace and before toasting the King: a scene that might have been even more impeccably Edwardian had their socks and underwear not dangled over their heads, drying on the stove pipes.

It was in that wardroom, on March 21, 1902, after cherry brandy and cigarettes, that the plans for Scott’s most ambitious diversion—an illustrated periodical—were unveiled. Albert Armitage, the Discovery’s navigator, recalled the discussion:

It was to be published on the 1st of each month; and every member of the ship’s company was invited to contribute towards making it the most amusing, instructive, up-to-date journal, with the largest circulation of any periodical within the Antarctic Circle. It was to combine all the best qualities of the penny and halfpenny London dailies, together with those of the superior comic papers, as well as of the fourpenny-halfpenny and half-crown monthly magazines. Notwithstanding this super-excellence, The South Polar Times was to be issued free to all the population of our small colony, the cost of production being more than covered by the grateful feeling of the recipients.

Editor Shackleton, whose literary credentials included the co-authorship of a fifty-nine-page volume on a Boer War troopship and the frequently expressed conviction that Browning was a better poet than Tennyson, soon hung up a mahogany letter box, carved with a bas-relief of the sun disappearing beneath the horizon and the words

DISCOVERY

1902.

Potential contributors were instructed to drop their submissions—poems, humorous essays, and scientific articles, all on Antarctic themes—into the box, their identities concealed by noms de plume. “[W]e agreed that the cloak of anonymity should encourage the indulgence of any shy vein of sentiment or humour that might exist among us,” wrote Scott, whose own humor—which was more evident on paper than in person—was indulged by four pseudonyms: “Experto Crede” (Trust the Skilled), “Ignotus” (Unknown), “Glossopteris Flora” (an Antarctic fossil), and, when he composed the Monthly Acrostic, “Cross Stick.”

S.P.T. Letter box, South Polar Times, April 1902, inside back cover. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Unlike the wardroom, the South Polar Times was open to both officers and, as Scott referred to them, “the humbler members of our community who dwelt before the mast.” Armitage wrote:

On most days during the first month of the winter the clicking of the typewriter could be heard in Shackleton’s cabin as he busily “set up” the paper; and frequently a shy and conscious-looking blue-jacket [seaman] would enter the editor’s sanctum to ask that worthy man’s advice.

Shackleton was so beleaguered by would-be men of letters that he relocated the editorial office from his cabin to a storeroom in one of the holds, installed his typewriter on a packing case, and attached a rope to the door so that, if he wished to work undisturbed, he could yank it shut from his seat (another packing case).

Shackleton’s magazine represented the convergence of several lines of journalistic influence. Winter periodicals had been a staple of British Arctic expeditions since 1819, when William Parry, on his search for the Northwest Passage, established the North Georgia Gazette, a shipboard newspaper that published the work of “The Sportsman and the Essayist, the Philosopher and the Wit, the Poet and the Plain Matter-of-fact Man.” (Non-Brits tended to scoff at expedition periodicals. The Icelandic-American explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson called them “busywork newspapers” and said they made men soft.) The S.P.T. also owes a conspicuous debt to popular satirical magazines such as Punch, of which the Discovery library had thirty-five volumes. But as the Antarctic historian Roland Huntford has pointed out, what the S.P.T. most resembled was a school magazine. The travel accounts, science articles, nature odes, verse parodies, and self-deprecatingly humorous essays of the Alleynian—the magazine of Dulwich College, which Shackleton attended until he left for the mercantile marine at sixteen—are deeply S.P.T.-ish, except that the Dulwich boys tried to sound like men, whereas the Discovery men often tried to sound like boys.

April 23, 1902, was “a notable day,” according to Armitage, “for it marked the disappearance of the sun, a total eclipse of the moon, and the début of the South Polar Times.” The first issue was presented to Scott at dinner in the wardroom, and a bottle of brandy uncorked so the officers could drink to the magazine’s success. Shackleton, a man infrequently given to exclamation points, recorded in his diary that the fruits of his labors were “greatly praised!”

In fact, the South Polar Times was the object of such keen interest that what Scott called “a rather delicate situation” arose: the mahogany box overflowed with more manuscripts than the magazine could accommodate, thus leading to the “danger of wounding the feelings of those literary aspirants whose contributions were rejected.” Shackleton’s politic solution was a supplementary journal called the Blizzard. Unlike the first-string South Polar Times, which appeared with hand-painted illustrations in a meticulously typed edition of one, the Blizzard was printed, in an extravagant run of fifty, on an Edison mimeograph. But the competition was too stiff. The Blizzard, universally recognized as the inferior publication, folded after a single issue.

Shackleton edited four more issues of the South Polar Times, which were passed hand-to-hand both in the wardroom and on the mess deck. Scott recalled:

I can see again a row of heads bent over a fresh monthly number to scan the latest efforts of our artists, and I can hear the hearty laughter at the sallies of our humorists and the general chaff when some sly allusion found its way home. Memory recalls also the proud author expectant of the turn of the page that should reveal his work and the shy author desirous that his pages should be turned quickly.

In late 1902, while the South Polar Times was on its summer hiatus, Scott, Shackleton, and Edward Wilson, the assistant ship’s surgeon as well as the magazine’s chief illustrator, left on a 960-mile sledging journey that took them within 410 miles of the South Pole—the farthest south any man had yet traveled. They all developed scurvy. Shackleton’s case was the most serious, and, after he returned to the Discovery coughing blood, he was invalided home, against his wishes, on a relief ship. (He recovered sufficiently to lead three Antarctic parties himself, including the Endurance expedition, a series of heroically averted disasters that culminated in an 800-mile voyage across the South Atlantic in a lifeboat.) The winter after Shackleton’s departure, a Tasmanian physicist named Louis Bernacchi was elected the second editor of the South Polar Times. During his three-issue tenure, Bernacchi’s most valuable contributions to the magazine were recognizing that Shackleton had found a winning formula and having the good sense not to mess with it.

Events of the Month, South Polar Times, April 1903, p. 36. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Scott returned to Antarctica on the Terra Nova in 1911 to attempt the South Pole one more time. The South Polar Times was revived for four issues during the winters of 1911 and 1912, under the editorship of Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the assistant zoologist, a near-sighted country squire whose chief qualifications for the job were five years of translating Greek and Latin at Winchester and a cousin who edited Cornhill Magazine. As soon as Scott accepted Cherry-Garrard on the expedition, he gave the new recruit his first assignment: learn to type.

***

I first heard about the South Polar Times nearly forty years ago. I read a few paragraphs about it in an Antarctic biography when I was in college, and my ears pricked up so energetically—Twilight of an empire! Journalistic history! Polar heroes as editors!—that I briefly considered it as a topic for my senior thesis. But I’d never seen it. Hardly anyone had. The originals are divided among three institutions in London and Cambridge. Two hundred and fifty copies of the Shackleton and Bernacchi issues were published in two volumes in 1907, and 300 copies of the Cherry-Garrard issues (except his last one) in 1914; a combined three-volume set is now available online, from Antipodean Books, for $27,500. Another 350 copies trickled out in 2002, followed by 500 copies of the S. P. T. ’s final issue in 2011.

In 2012, to celebrate the centenary of Scott’s death, all twelve issues were reprinted by London’s Folio Society in a facsimile edition of 1,000: a veritable Niagara. The Folio Society publishes things like Brave New World bound in aluminum foil and Lost Illusions bound in crushed silk. When the edition of the South Polar Times was announced, a member of an online forum wrote, “Oooooooh fudge. I bet this is going to be hideously expensive.” It was: £495 in England, $945 in the United States. The price has proved no deterrent. All but 32 sets have been sold.

When the parcel containing the review copy arrived, I washed my hands before I opened it, having never harbored a book in my house that cost as much as a used VW. I also braced for disappointment, knowing that things you’ve pictured for decades are never as good as your imaginings.

It was even better.

Past editions of the S.P.T. have lumped an entire year’s output into a single beefy volume. This is the first time that each issue has been printed separately, so that when you turn the acid-free pages (perhaps, for verisimilitude, after crawling into your freezer with a paraffin lamp), you can approximate the experience of reading it hot off Shackleton’s typewriter. The twelve softbound issues, New Yorker-sized but with square spines, repose in a gray canvas box with a magnetic clasp that closes with a luxuriously resonant click; there is also a slipcased hardbound volume of useful commentary by the polar historian Ann Savours.

All the illustrations are charming, but the title page of the first issue is irresistible: a mock coat of arms whose escutcheon is flanked by two Emperor penguins; backed by a sledge and skis; and surmounted by a tasseled balaclava on which a McCormick’s skua perches, its wings outspread as if it is about to fly off the page. Like most of the illustrations in the S.P.T. , it was the work of Edward Wilson, the Discovery’s assistant surgeon and vertebrate zoologist. Today it would be a happy accident if an expedition scientist were also an artist; before photographers went along, it was the norm.

Edward Wilson, South Polar Times, April 1902, title page. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Wilson was especially fond of penguins. (So were the members of most British expeditions. Over the next decade, the Scottish Antarctic Expedition serenaded them with bagpipes, the Nimrod Expedition with a gramophone, and the Terra Nova Expedition with a rendition of “God Save the King.” Antarctica had no natives to civilize, but at least one could attempt to convert the penguins into good British colonials.) He attempted to raise an Emperor penguin chick in his cabin, rising at 1:00 and 5:00 a.m. to feed it pre-chewed seal meat. Wilson’s penguins frolic through the pages of the South Polar Times, waddling, preening, swimming, incubating eggs, brooding chicks, and, in one case—decades before it had become a cliché—wearing evening dress, complete with black tailcoat, white waistcoat, poke collar, and white bow tie. Wilson sketched them en plein air, because, although he was a trained taxidermist, he preferred live models. (“Dreadful stuffed birds!” he once wrote his fiancée. “No one would think of painting preserved flowers—why on earth do they paint preserved birds?”) In temperatures below -30°, his eyes inflamed by snow-blindness, he ungloved his hands for a few minutes at a stretch to draw with a soft pencil, making shorthand notes on the colors he planned to add when he came in from the cold. (“Pr. b.” was Prussian blue.)

Edward Wilson, detail from “Ode to a Penguin,” South Polar Times, May 1902, p. 29. © Royal Geographical Society (with IBG).

Wilson also contributed Turneresque icescapes; caricatures of expedition members in the style of “Spy,” the Vanity Fair cartoonist; and paintings of the officers’ sledging flags, swallowtail pennants with heraldic insignia and mottos in English, French, Latin, Maori, and Hindustani. His own motto was Res non verba (Deeds, not words). In fact, he was good with words, too. His “Barrier Silence,” about whether God had intended man to learn the secrets of the Antarctic, was one of the S.P.T. ’s better serious poems—though it must be admitted that most of the competition was godawful (“Her crew are Britons to a man, her name ‘Discovery’, / That England still shall set the pace as Mistress of the Sea”). On the other hand, the magazine’s light verse—“Summer Sledging in Sledgometer Verse,” “The Ballad of the Seal & the Whale,” “To a Reversible Thermometer”—displayed a close acquaintance with the work of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, not to mention a sound background in metrical forms. It was hilarious. The S.P.T. also featured Scott’s acrostics, none of which I could solve; knowledgeable disquisitions on Antarctic geology, ornithology, and marine biology; Meteorological Notes; Events of the Month (“April 23. First number of ‘South Polar Times’ issued.” “May 2nd. Heavy gale.” “May 5th. Dr Koettlitz discovers Bacteria in a seal’s intestines.”); and Editor’s Notes, which covered such topics as conversation in the Discovery wardroom:

The following subjects have been thoroughly sifted during the past month at the dinner table of the British National Antarctic Expedition:—

The capability of Peacocks to stand an English winter.

The cultivation of Tea and Indiarubber.

The advisability of saying “Good morning” at breakfast.

Glacier action in Antarctic Regions.

Crinolines, and the chance of their revival.

The word “fact” as a synonym for “probability”.

Schopenhauer’s views on Womanhood.

Terra-cotta Tablets and Lime-juice nodules.

The bottom of a tumbler.

The treatment of absurd statements by “smuggindifference.”

The influence of Poetry on certain people,

and

The braying of an ass.

***

Above my desk hangs a Xeroxed photograph of Apsley Cherry-Garrard in the Terra Nova Expedition’s hut at Cape Evans. He sits at a table in a woolen sweater, typing out an issue of the South Polar Times on an Underwood No. 5. A photograph! One of the differences between Scott’s two Antarctic expeditions is that on the second he brought a photographer, Herbert Ponting, who set up a darkroom with a lead-lined sink for developing glass plates. Cherry-Garrard’s four issues of the S.P.T. are illustrated not only with exquisite watercolors by Edward Wilson, now the chief scientist, but with photographs of Emperor penguins, a Weddell seal, an iceberg, and a sled dog. No photos of human subjects made it into the magazine, though in a song called “Pont, Ponco, Pont,” the S.P.T. introduced the verb “to pont”: expedition slang for “to be forced to pose in an uncomfortable position.”

Cherry-Garrard was an assiduous editor who not only solicited anonymous contributions but assigned pieces and asked for revisions. His first issue debuted on June 22, 1911: Midwinter Day, a traditional holiday on polar expeditions. After lunch, he presented the magazine—fifty pages of typescript, bound between sealskin-edged plywood covers, to Scott, who read most of it aloud to the assembled men, whereupon they tried to guess who had written what. “I fear no one thought I had done ‘Valhalla,’” recalled Thomas Griffith Taylor, the expedition’s senior geologist, “which is a mixed pleasure—for all seem to enjoy it; while Nelson put down the ‘Protoplasmic Cycle’ to Debenham, though he actually read the verse in the Pack in my diary!” The celebration continued with a festive dinner whose menu was published in the following issue:

Midwinter Day, South Polar Times, September 1911, p. 40. © British Library.

Even Scott got drunk.

It is easy to mock the men who ate those mince pies and plum pudding. When you read the South Polar Times, Scott’s famous 25 x 50-foot hut at Cape Evans—with its series of “Universitas Antarctica” evening lectures (on geology, parasitology, Mendelian genetics); its good-natured razzing (girls’ nicknames, Latin jokes, gibes about snoring and bunk décor), and its well-defined strata (officers and scientists at one end, “men” at the other, bulkhead of crates in the middle)—sometimes sounds like a cross between Toad Hall and a public school dormitory.

Excerpt from “The House That Cherry Built” (poem by Henry Bowers), South Polar Times, September 1911, p. 32. © British Library.

But the social machinery worked. The S.P.T.—along with the music and the games and the books—dispelled the winter gloom, just as Scott had planned. As the wardroom/mess-deck distinctions on the Discovery had promoted what Bernacchi called “an atmosphere of civilized tolerance,” so the hut’s code of gentility and wit permitted its tenants to behave as if they were having a ripping time on their hols instead of waiting for sledging journeys that might kill them.

Five days after their first issue debuted, Apsley Cherry-Garrard and Edward Wilson, along with Lieutenant Henry Bowers, left on one of those journeys, marching through the darkness in temperatures as low as -77° on an expedition to collect the eggs of Emperor penguins, whose embryos were (erroneously) thought to represent a crucial evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. The men’s clothing froze into armor; their teeth cracked and shattered; the fluid inside their frostbite blisters turned to ice. In The Worst Journey in the World, Cherry-Garrard’s classic 1922 account, their ordeal sounds like hell. But in the S.P.T., Bowers leavened the worst part of that worst journey—the hurricane that blew away both their tent and the canvas roof of their stone igloo, leaving their survival in grave doubt—into a pastiche of “This Is the House That Jack Built,” four pages of doggerel about a storm that scattered “parts of the cooker, and gloves and socks, / A muddle of sleeping bags, men and rocks, / Primuses, oil-cans, penguin skins, / Eggs and pemmican, biscuit tins.”

Four months later, Scott, Wilson, and Bowers, along with Titus Oates and Edgar Evans, sledged to the South Pole, only to find that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had beaten them there by thirty-four days. Amundsen’s men had spent the winter in a hut, too, 420 miles east of Cape Evans—but they were too busy making their dog whips and remaking their boots and planing their sledge runners to do much talking or publish a magazine. Amundsen’s party of taciturn pragmatists survived: Res non verba. On the way back from the South Pole, Scott and all four of his companions died of starvation, scurvy, and hypothermia.

Cherry-Garrard and a skeleton crew of twelve were waiting at the Cape Evans hut. When Scott’s party failed to return, they knew all five men must be dead. The only way to make it through the winter of 1912 was to pretend they didn’t know. As Frank Debenham, one of the expedition’s geologists, later explained, “It has been tacitly accepted that the tragedy of the autumn must not intrude itself upon us, and consequently we are able to throw it off at times and behave as if it were not intruding.” Cherry-Garrard put out one last issue of the South Polar Times. It made not a single mention of the elephant in the room. There were no illustrations by Wilson, of course, but Debenham, whistling in the dark, contributed a series of pen-and-ink sketches of penguins playing rugby.

When he returned to England, Cherry-Garrard allowed his other South Polar Times issues to be published, but he kept the last one to himself. It was not made public for nearly a century. The official word is that it was withheld because its quality was inferior, and that is certainly true. But I can’t help wondering if Cherry-Garrard was embarrassed that while Scott was suffering and dying on the Great Ice Barrier, he was sitting at his Underwood No. 5, typing up a quatrain about blizzards in the style of Walt Whitman. Of course, that is exactly what Scott would have wanted him to do.

Detail from “The Weather,” South Polar Times, June 1912, p. 22. © Scott Polar Research Institute.

NOTE: The editors would like to thank The Folio Society for its generous assistance. All images reproduced courtesy of The Folio Society.

Published on April 11, 2019

First published in Harvard Review 43