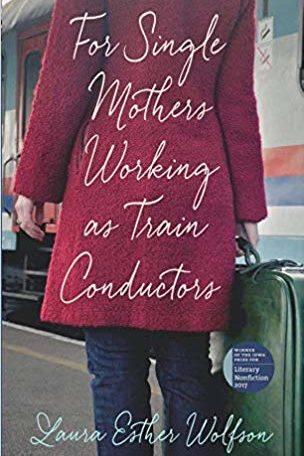

For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors

by Laura Esther Wolfson

reviewed by Laura Albritton

Laura Esther Wolfson’s collection of personal essays, For Single Mothers Working as Train Conductors, was awarded the Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction for 2017. In thirteen essays, Wolfson narrates episodes from her own life and meditates on a range of subjects including marriage, Judaism, illness, her desire to have a child, the intricacies of translation, and the limitations of language. An interpreter and translator of considerable international experience, the author leads readers to Russia, Paris, and New York, at various points in time, as she reflects on the vicissitudes of her adulthood.

The volume begins in the Soviet Union, with Wolfson describing her first marriage. We are plunged into a discussion of pregnancy, babies, and birth control, in which we learn that diaphragm birth control is a rare commodity in Soviet Russia; one woman “married to a man who didn’t like condoms— isn’t that redundant? – had thirty [abortions].” The sad irony is that Wolfson, an American with access to all the birth control she might want, wishes to get pregnant, although her Russian husband insists they put off having children. Later, in the United States, he persists in finding excuses not to have a child. In direct, conversational prose that highlights her exasperation, she writes, “Six years we’d been married. We had good jobs and a large apartment. Exactly what did we still need to do? Buy a crib? Diapers? Just what was missing?” The unusual syntax of the first sentence suggests that we might be reading a translation; the foreign-sounding word order underlines not only that much of their relationship is conducted in another language (Russian) but also that their different cultural backgrounds at times act as a wedge between the couple. The essay closes as Wolfson, now divorced from the (as yet) unnamed Russian husband, learns that he has had a baby with his second wife.

Loss and disappointment haunt the memoir just as dreams of last czar Nicholas II might have haunted a White Russian. The book brims with reproach: in some cases, the essays reproach her two ex-husbands, a landlord, or an employer, while in other instances, the author reproaches herself. In “The Husband Method,” for instance, she reveals more about her marriage to her first husband, and uncovers clues about what led to its eventual demise. Looking back, she realizes that telling people about her husband’s compulsion to repair gadgets he found in the garbage had in fact “shamed him—blindly, foolishly, inadvertently—in a way that transcended language.”

The book’s reproachfulness towards others can be quite intense—yet not without justification. In the Paris-based essay “Montmartre,” Wolfson is diagnosed with a serious, degenerative lung disease. A French surgeon delivers the news that she will eventually need a lung transplant, although, “It wouldn’t be for another fifteen or twenty years. And many women with this condition don’t live long enough to need one.” Often, conversations in memoirs must contain approximations; however, in this case, one can imagine the surgeon’s callously blunt comment lodged in the author’s memory for years, only to spring forth in this essay, a small gesture of reprisal.

Wolfson’s lung disease means that, back in New York City, she needs a job with good health insurance. While the essay “Proust at Rush Hour” ostensibly chronicles how the author reads In Search of Lost Time on the subway, it also depicts how her illness traps her in an unrewarding position with an unnamed organization (presumably the United Nations, where Wolfson worked once). First a freelancer, she “tumbled down and down in status and job satisfaction” until awarded a permanent position which made practically no use of her expertise in Russian and French. A more desirable position, as the author points out in witty, reproving commentary, would require “a different sort of fluency altogether, directly proportionate to the climber’s ability to say nothing and offend no one, in the most elegant way possible, all at great length.” To emphasize this criticism, she quotes from an administrator’s email written with ridiculously labyrinthine politesse—a forceful way to illustrate her frustration.

One of the most emotionally fraught essays, “Fait Accompli,” functions as an indictment of her first husband. Wolfson recalls a trip they took to the Caribbean, where she raises the subject of having a child, only to be told “Please … don’t spoil my vacation.” If she gets pregnant by accident, he asserts that she must get an abortion: “Our baby must be planned.” Again, one senses these recollected conversations are verbatim; the passages vibrate with pain. The full consequence of her first husband’s delays emerges years later, when Wolfson and her second husband are trying to conceive. Her lung collapses, and a specialist advises that given the severity of her disease, getting pregnant would endanger her life. “There were further consultations, a second opinion, a third,” Wolfson confides, but “Everyone agreed.” With those two stark words, she conveys the full hopelessness of the situation.

While this personal tragedy preoccupies a good portion of the memoir, a major professional lost opportunity appears near the end, in “Losing the Nobel.” We learn that at a time when Wolfson’s health was especially bad, and she doubted her abilities, she turned down translating a book by Svetlana Alexievich—who eventually won the Nobel Prize. She writes, “It is not good to dwell on what might have been: the participation in something meaningful, the inherent satisfaction, and yes, the honor and prestige, and perhaps a modest financial windfall – these could-have-beens, catalogued from the most important down to the least.” While the author wants to avoid “batter[ing] myself with recriminations over the Nobel,” that is what she does in the course of the essay. She defends her choices (“I chose my writing over hers – isn’t this what creative people are supposed to do […] ?”), and then condemns them (“This does little to assuage my regrets”).

In the essay “The Book of Disaster,” focus jumps from subject to subject: Yiddish, Holocaust survivors, translation, literary agents, and books that do not get published. Skillfully weaving together disparate narrative strands, Wolfson displays a deep capacity for compassion when it comes to someone else’s misfortune. It will be interesting to see if, in her next book, the author turns from memoir to the stories of others. At the end of the volume, Wolfson asks: “Of all the mutually incompatible, contradictory things I had done at various times, which ones should I continue doing, and from which of them should I desist?” With this, the writer contemplates not her past, but the unknown future.

Published on April 11, 2019