At the Picture Window

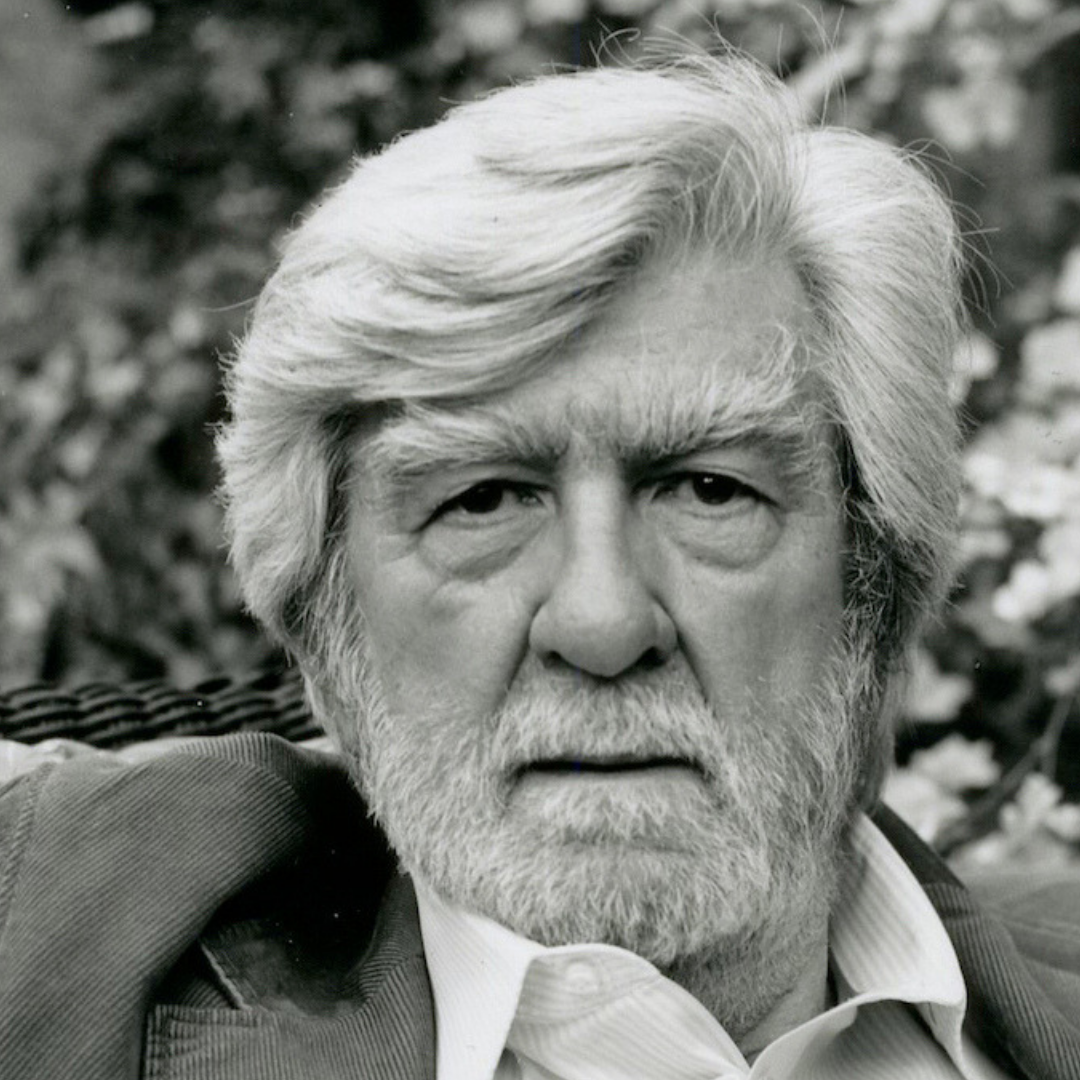

by Stanley Plumly

Then there’s the maple,

still filled out in brick-brown reds and rust,

a few leaves, big as hands, falling, drifting,

then, on a different day,

nailed by the rain to the lawn.

When I was alive, when I was a daydream,

I’d sit in the window’s three-cornered bay for hours,

for the thought of it, the secret of it,

the glass and separation,

and if for nothing else the view—

how old was I?—

a farm light here and there now coming on,

the twilight turning deeper bluer blue,

then a childish number of the visible stars.

Then, suddenly, first thing in the morning,

the dry and yellow acres of ripe September corn,

fluttering like paper

along the shadow angles of the sun.

Then the sun overhead.

And after school the wasted afternoons,

not a live soul or dead soul anywhere,

except the Amish on their way to mystery

in their elegant cab carriages,

the horses’ hooves like clockwork on the asphalt,

a worn-out pickup truck or tractor with its load

slowing to a walk behind them.

Part harvest, part emptiness . . .

Across Scott Garbry Road a brake of brush

and two white oaks that by the early frost

would ring with the madding chatter

of every kind of blackbird, black on black

especially when the guns went off

and the birds rose in swarms of smoke and scattered—

they’d be back, some would, the next blue dusk,

then disappear again, dark and darker,

into the pale night sky,

echoing the sounds of what they were.

Which is why my mother loathed the trains,

their hollow distances and silences between,

trains in the winter,

close enough to see and far enough

to hear their long passing heartbreak

carried by the cold,

floating on the ice and perfect snow,

right up to the porch and through our seven rooms.

Published on December 5, 2013