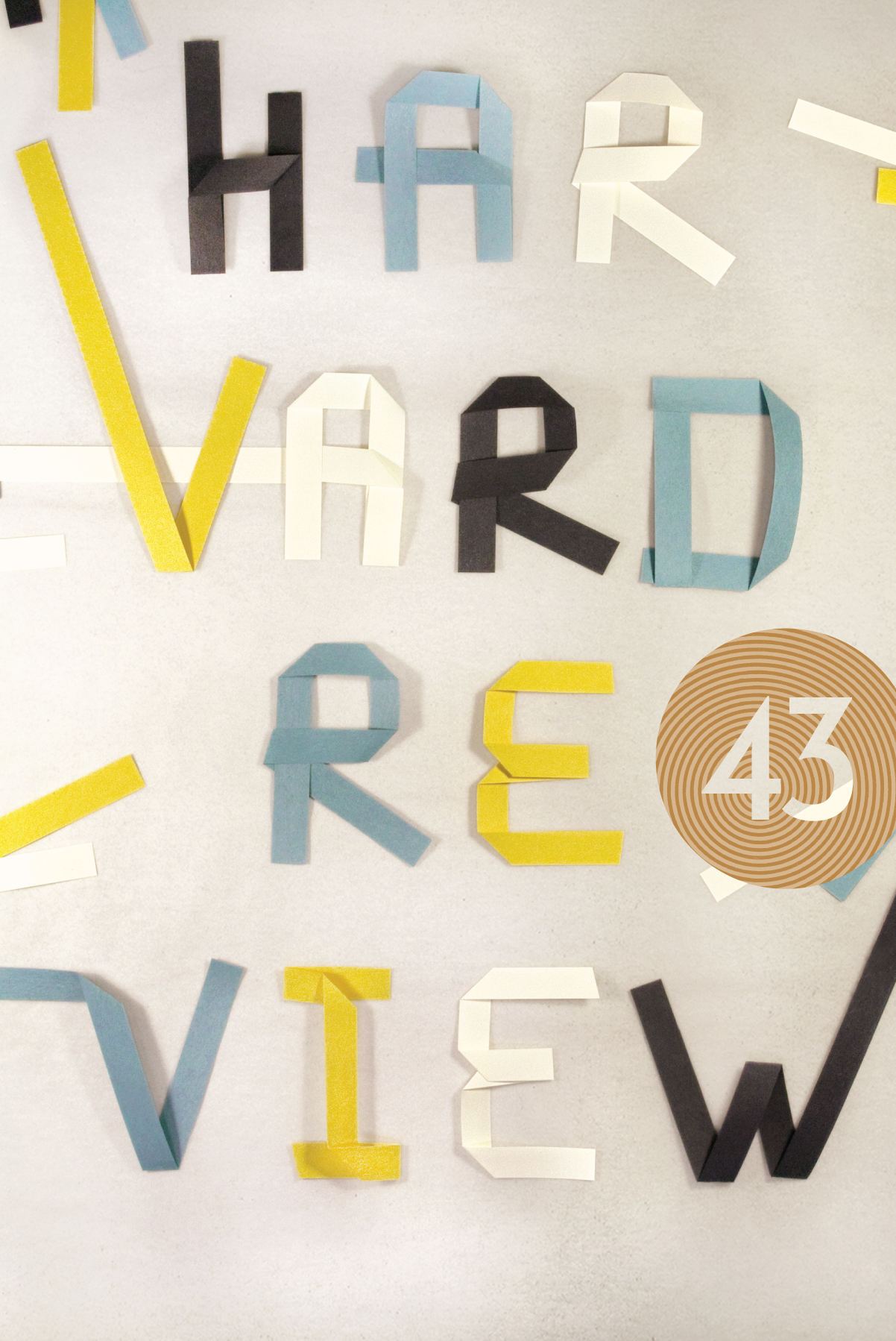

HR 43 Editorial

by Christina Thompson

Harvard Review 43 is a curiously personal issue for me. To begin with, it contains work by two people I have wanted to publish for many years. The first is the Australian novelist Michelle de Kretser, whom I have known for more than two decades and from whom I first tried to coax a story about fifteen years ago—before she had even published her first book. She has since gone on to write four fascinatingly different novels, including the recently published Questions of Travel and The Lost Dog, which was longlisted for the 2008 Man Booker Prize.

The second is the wonderful editor and essayist Anne Fadiman, author of the award-winning The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down and two collections of essays, Ex Libris and At Large and At Small. I have been an admirer of Anne’s for well over a decade, ever since I first heard her speak at a Nieman Narrative Journalism conference, and I have been gently tugging at her ever since for something we could publish in Harvard Review.

But there are other odd forces at work here as well. The essay Anne offered us was the story of the South Polar Times, a magazine published by Robert Falcon Scott and his companions as a form of entertainment during the cold, dark months as they overwintered in the Antarctic. By a strange coincidence, I had just read another wonderful essay written by someone who had actually been to Antarctica and had peered into the dim recesses of Scott’s hut. This one was by one of my students, a planetary scientist named Sarah Stewart Johnson, who, so far as I know, has never published a literary essay before.

It was too serendipitous to be ignored. But then, in a mad dash to secure art for the issue—our art editor having had an accident that temporarily put her out of commission—a friend mentioned to me that Heddi Siebel, a well-known local artist, had some unpublished photographs of an early-twentieth-century Arctic expedition of which her grandfather had been a member. While even randomly sourced content has a tendency to “cluster” when one is putting an issue together, this was definitely a more remarkable grouping than most.

I also have a strong feeling of coincidence about the first piece in this issue. Vicky Grut is a writer who is new to us, and her essay, “Into the Valley,” came in the mail along with hundreds of other unsolicited pieces. But I happened to read her plain, moving account of what it is like to sit with someone who is dying just months after my own mother had died. I recognized at once the truth of the essay: the fear that such a situation engenders, the courage it inspires, the terrible irrevocability, and above all the otherworldliness of that close proximity to death.

The issue is not completely filled with liminal settings and dark, transcendent experiences, however. There is humor and politics—even in combination—as well. The fine Canadian novelist Judith McCormack returns to Harvard Review with a witty story about two young lawyers on a trip to Sicily, and Angela Morales, another writer we have just discovered, recounts a hilarious story about the ERA in the 1970s from the perspective of a sixth-grade girl. It is also a point of some interest that the prose sections in this issue are dominated by women. All of the essays and five of the six stories have female authors, and even the story by Adam Braver (the only male) is called “What the Women Do.”

Finally, while I am in this elegiac mood, I want to take a moment to thank someone who has been a tremendous friend to Harvard Review. Dean Michael Shinagel, who is retiring after a long and distinguished career with the Division of Continuing Education, has helped us in so many ways, providing advice, support, ideas, contacts, even book reviews. We will miss him exceedingly, but I’m sure he’ll be busy—traveling, lecturing, writing! We wish him the very best and extend our deepest gratitude for all that he has done over the years for Harvard Review.

Published on February 19, 2015

First published in Harvard Review 43