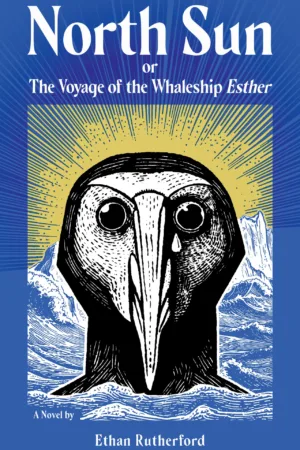

North Sun, or, the Voyage of the Whaleship Esther

by Ethan Rutherford

reviewed by Katy Dycus

The year is 1878, and we are in the final days of the American whaling industry. The Esther is setting out from New Bedford, Massachusetts, which was, in the mid-1800s, the largest whaling port and wealthiest city in the world per capita. Aboard the Esther, we enter an environment like that of Captain Ahab’s whaler in Moby Dick, one rife with strange events, exciting yet violent chases, and stretches of boredom and loneliness. We watch men who profit from the riches of the industry and, in so doing, determine the course and value of human lives and those of the sea creatures lurking below.

This is the setting of Ethan Rutherford’s new novel North Sun, or The Voyage of the Whaleship Esther, written in the tradition of the classic sea-voyage narrative while creating its own mythos. When I began reading North Sun, I listened to parts of Peter C. Murray’s scored audiobook, which provides a strange, thoughtful soundscape to the narration. Even without the musical accompaniment, though, I soon came to realize that North Sun itself is a composition made up of haunting melodies. Rutherford’s lyrical, spare prose has a cadence like the movement of the sea. His imagery offers just enough to sketch out the beautiful yet unforgiving nature of the Arctic North.

A Persian proverb came to mind while pondering this landscape: “He who wants a rose must respect the thorn.” The sea is stunning, yes, but riddled with hidden dangers. The whalers must respect the perils of the journey, the wildness of their seemingly tame and timid prey. A lack of respect spells defeat. Indeed, in seeking to take down the great beasts of the sea, the men simply destroy themselves. They take from the natural world and from each other, unaware of the collective and personal costs of such ruthless exploitation.

Despite their material wealth, the men are existentially barren. They experience a paradoxical emptiness as vast as the sea. The ship is loaded with barrels of whale oil, yet the men aboard are isolated from one another. The ocean is full of whales, sharks, krill, squid, and tuna. But in one scene, two young brothers—whose perspectives we rely on throughout the narrative—peer into the water and see only impenetrable blue darkness: an absence of color, light, and warmth.

Rutherford’s book seems to ask: how far will man sink in pursuit of fill-in-the-blank? On its surface, this is a story about men chasing profit, seeking to extract the things that make the whales commercially valuable: sperm oil, whale oil, baleen, whalebone and occasionally ambergris. The Ashleys, owners of the Esther, famously make and burn candles derived from spermaceti; products of a shady industry, these candles literally drive out the darkness.

But more spectacular and tragic, perhaps, are the countless other desires driving individual characters: glory, pleasure, radical acceptance, duty, revenge. And they often don’t even understand the true motivation behind their actions. For instance, Captain Arnold Lovejoy is hired to retrieve a mysterious golden egg from another whaling captain, Leander, whose ship has sunk beneath the Arctic waters. As the whalers sail northward to their final destination in the Chukchi Sea, ice closes in on the Esther. Captain Lovejoy embarks across the ice on foot in relentless pursuit of the egg. Unaware of its value, he nonetheless tracks it down and is a willing accomplice to murder in its attainment.

North Sun is a painful book. You ache while reading it. The sole sense of hope seems to shine forth from the only characters worthy of its light, the two nameless boys aboard the ship, for they do not take from anyone or anything. For this, they are rewarded by Old Sorrell. The closest thing to a divine figure, the half-bird half-man serves as the boys’ protector and brings an allegorical dimension to North Sun. His omniscient qualities offer the boys comfort as they seek his presence more and more. Like God himself, Old Sorrell decides when to kill and when to destroy, but also when to be kind, and to whom. It is the children who deserve his kindness, and he ultimately rewards them with the “relief in being alive.”

The book asks: “What dreams visit such survivors? When one does not know what he has seen versus what he’s already dreamed?” This unsettling uncertainty of experience, of memory, haunts the boys for the rest of their lives. When we later visit the boys as old men, they don’t talk much about the Esther, or what they endured aboard it. But we are told they never forget the visceral details of that voyage: the “salt-grit of the wind,” “a sperm whale arching his clumsy back,” “diatoms constellated like stars.” More importantly, they never forget the fact that they’d had one another. Loneliness and death shudder and crack, yielding, as it were, to the weight of Arctic ice, and the boys are given the double gifts of being alive, together.

Published on April 14, 2025