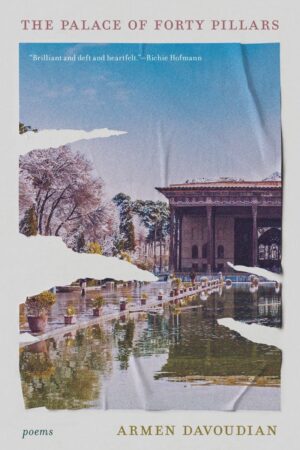

The Palace of Forty Pillars

Armen Davoudian

reviewed by Ananya Kanai Shah

The Palace of Forty Pillars by Armen Davoudian is a deft and formally rich debut. Named after the Chehel Soutoun in Isfahan—a palace with twenty columns that appear to have forty when reflected in a fountain—this collection is preoccupied with mirroring (several poems utilize rhyme), preservation, and distortion.

The poems contradict, redact, and push one another. At the center of the collection is the speaker, a conjurer of dreamscapes across time with one ear to the ground and the other attuned to memory. He is a gay man of Armenian heritage raised in Iran and living in America, as well as a scholar of literature for whom Persian and English represent a “parallel-text tragedy,” the languages like “lovers whom an ancient grudge divides.” The text is both the pointed lament of an individual exploring transmutation and loss as well as an excavation of communal horrors such as the Armenian genocide and homophobia. This kaleidoscopic and ambitious collection braids family and Armenian history with James Merrill, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Persian works such as the Shahnameh (The Persian Book of Kings). Deploying literary forms like the ghazal, sonnet, and ruba’i (calling to mind Omar Khayyam), The Palace possesses a tensile and tactile beauty.

In the first section, “The Ring,” a series of shorter poems, including sonnets, offers the reader a glimpse of the speaker’s family dynamic, opening with images of his parents’ wedding to tackle the themes of belonging, familial expectation, and guilt. The third sonnet in the series imagines the speaker’s grandfather, a carpetmaker, alive again and strident on speakerphone:

“Stop that kid from reading. He’ll go blind.”

Unhappy in his body, the kid’s all mind,

or so he thinks, turning from life to books,

because he’ll never get by on his looks?

The rhyme—“blind” and “mind” and “books” to “looks”—heightens the stilted comedy in the grandfather’s exhortation. The rhymes reflect and collapse the distance between the here and there, the mind and body, and this movement enacts the motion in the speaker and the grandfather’s relationship. The preoccupation with perception and expectation is echoed in the volta:

He loves his mother and other boys too much

and everything he says will come out botched.

The second section explores the everyday realities of migration, unlocking both its indignities and tense beauty with irony. The poem “Saffron Rice” details a gathering where saffron rice like “studded gold” is served in heaps:

Piled like a treasure-hoard and studded gold,

mounds and mounds of it, and women hunched

in dark, silent bundles in corners here and there,

somebody’s live-in grandmother or widowed aunt

There is pathos in the irreverence of the “live-in grandmother” compressing poverty and anguish. The couplet, with its orderliness and necessary restraint, infuses a wry melodrama into the social collage. Elsewhere, “coy eligible girls” rinsed in rosewater find their way to the host’s spare room, where “stale old rugs” are stacked high to form guest beds. The musty room is undercut by the perfume and youth, just as the spectacle of rice is undermined by the women in “bundles.” The couplet lends a steady cadence to the poem.

“Vice Squad,” a ghazal halfway through the book, transforms the central motifs of the form—the beloved, separation from the beloved, the spiritual longing for a homeland transposed upon the beloved—into a memorial for the speaker’s mother and the costs of the genocide. This taut, highly controlled poem unspools into the mythic by invoking Lot’s wife:

When Old Julfa was burning and drunk on fear

–we’re still hungover—my hand was in yours.

You were the wife of Lot. I was the salt of your body.

Though I’m not a believer, my hand was in yours.

“Who speaks of the Armenians?” Let our gravestones crumble

so they can uncover my hand was in yours.

With the slow, measured refrain, the tone is both elegiac and tart. It is a nod to how violence echoes across generations. Addressing his mother directly, the speaker imagines her as Lot’s wife and himself as the salt, implicated by genocide’s long memory. The final couplet, which alludes to the title of a Najwan Darwish poem, conflates several decades of ethnic targeting, including the Armenian graves destroyed in Julfa through the late 1900s and early 2000s.

The Palace of Forty Pillars is a formidable debut. The text’s formal variations, rhyme schemes, and wry humor are nimble and never artful, suffusing the text with grace. The swerves in logic and agile turns in each poem are refreshing; they reflect on, remember, and rewrite this cruel, busy world with delicacy.

Published on September 10, 2024