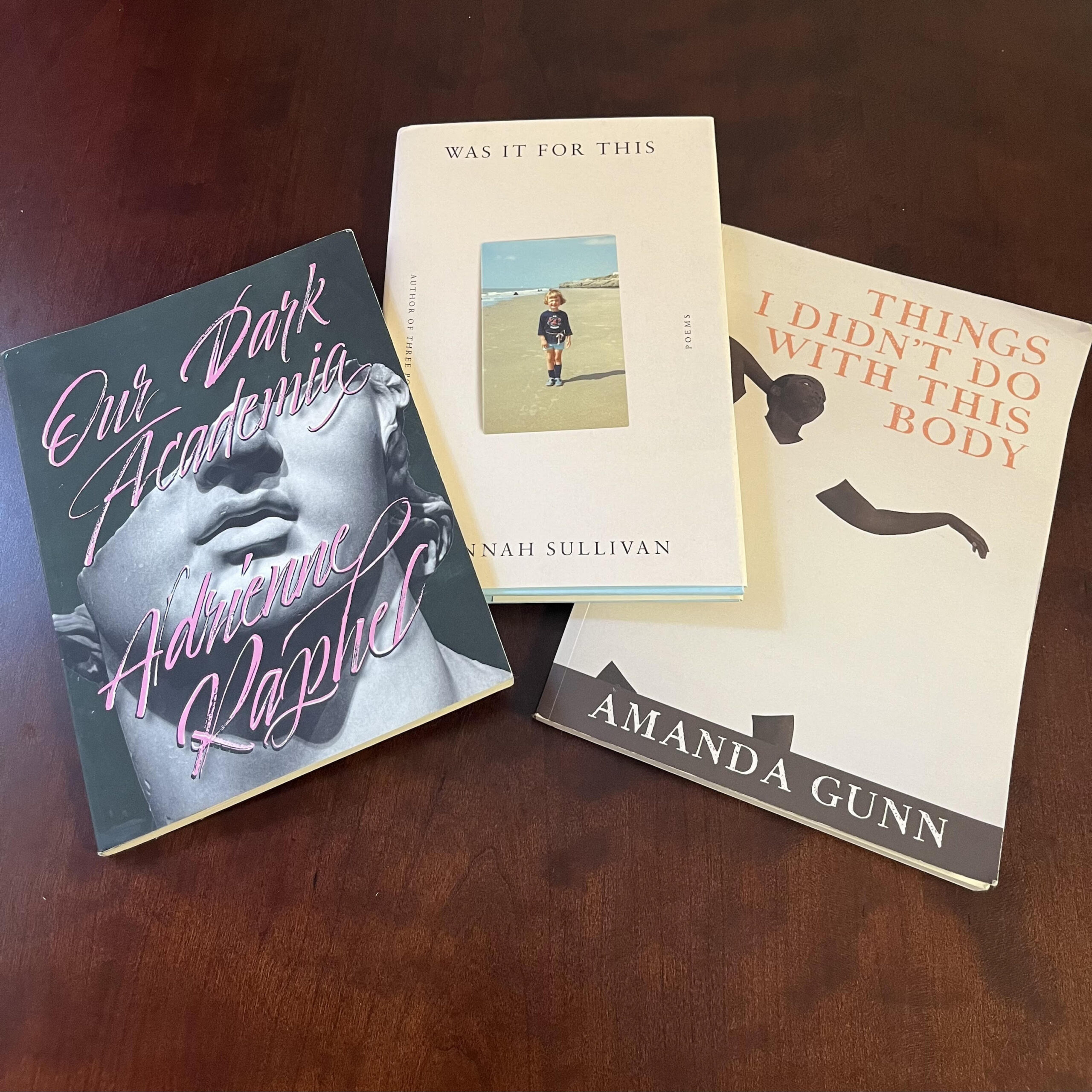

Three New Collections by Three Harvard Poets

by Andrew Koenig

On the surface, the connections between the work of poets Hannah Sullivan, Amanda Gunn, and Adrienne Raphel—all of them are graduates of Harvard’s doctoral program in English, and all of them released new collections this spring— may seem purely circumstantial. But a careful reading of their new collections, Was It for This, Things I Didn’t Do with This Body, and Our Academia, respectively, reveals deep resonances. All three poets explore the borderlands between the personal and the political. Whether it is through Sullivan’s deep engagement with the Grenfell Towers blaze, Gunn’s reckonings with American history, or Raphel’s quizzical riffs on internet culture, these collections search for meaning in a time of irrecoverable loss, doing so with elegance and pathos.

Sullivan’s Three Poems was a sleeper hit when Farrar, Straus & Giroux published it in 2018, the kind of book people lowered their voices to speak about, recommending it to friends like a well-guarded family recipe. In particular, “You, very young in New York” attained a kind of cult following, with its memorable use of the second person to mourn the end of youth: “You stand around // On the same street corners, smoking, thin-elbowed, / Looking down avenues in a lime-green dress / With one arm raised, waiting to get older.” Was it for this is continuous, in many ways, with Three Poems. In this work, whose title is an allusion to Wordsworth’s Prelude, Sullivan casts her mind further back, not to youth, but to childhood and the various influences, economic and political, that shaped her upbringing in Thatcherite Britain. The uniting theme of this book is housing: who has it, who doesn’t, how it is obtained and literally clung to for dear life. The book’s most ambitious sections are about the Grenfell Tower blaze, which killed nearly a hundred people. Sullivan connects this tragedy with others, whether epochal—Britain in rubble after the Blitz—or smaller forms of dispossession. The tragedy is never cheapened or sensationalized, and in her attention to the disgraceful facts of the fire, Sullivan achieves something often attempted but rarely pulled off: a political poetry that goes beyond the individual. Her poetry shows the political and personal are inseparable.

In “Tenants,” the first poem in the collection, Sullivan mourns a national tragedy and makes a scathing critique of flawed response efforts. With unsparing language, Sullivan gives a vivid picture of an apartment building whose materials and construction made it a death trap:

Before the fire, the firemen weren’t informed

That rainscreen cladding might be flammable,

Or that the staircase had been breached by drilling,

Which mean that smoke dense with particulate

Leapt choking up the only exit route,

Warping the melted plastic safety lights,

As water sluiced and fell in useless panes

And hoses tangled on the floor and melted,

Prising ajar the fire-resistant doors

That families had plugged with bits of cloth.

The poem then enters an unexpectedly sardonic register: Sullivan cites an official report whose neutral language is jarringly rendered in verse.

Firefighting operations were exceptional,

Dynamic risk assessment became requisite:

By 1am, ‘Stay Put’ should have been obsolete.

But this report is avowedly provisional.

We await further evidentiary material.

The decision to employ not just elegy, but also bitter irony and bureaucratese, lends this poem a multidimensionality well suited to the story of a building’s destruction. The contrast with “My Birthday,” the final poem in the collection, could not be starker. “My Birthday” considers a bunch of things that turn forty-one in light of the poet’s forty-first birthday: “What else: the sum of two / adjacent squares, the dialing code / for Switzerland and Mozart’s / final symphony in C / the sublime Jupiter …” The lightness and archness of this final section marks a departure from the opening poem, although irony is a shared feature. Sullivan’s willingness to employ humor and whimsy is refreshing; in spite of the heavy subject matter, the collection has a translucency to it.

Sections of Was It for This, especially “America, 2000s,” feel familiar. Anyone who’s spent time in a college town will understand the particular rhythms of school, idleness, and precarity described here. But it is the reflections on Grenfell, childhood, and motherhood that mark a new stage in Sullivan’s poetry. It’s bold to title a collection after Wordsworth’s Prelude, subtitled the “growth of a poet’s mind.” His influence is detectable in the inclusion of prosaic details such as the buying and selling of houses, the consumption of news, even the ekphrastic viewing of a YouTube video (a recent trend, memorably deployed by Sally Wen Mao in her 2019 collection Oculus). Like Wordsworth, Sullivan has gathered a lot of disparate material in Was It for This, and the book occasionally strains under the weight of it all. But what she achieves is a contemporary elegy to home, to what Sullivan calls “the vacancy [that] always was, / The eagerness with which all things disperse.”

Like Was It for This, Amanda Gunn’s collection, Things I Didn’t Do with This Body, strikes a balance between the personal and the collective. Reading Gunn’s and Sullivan’s collections together, I found myself seeing unexpected threads of interconnection—the desire to tell not just one’s own isolated history, but to understand it as bound up with the lives of others; reflections on the perils of motherhood; and the long shadow motherhood casts on those who never become mothers, or who have lost their children to tragedy.

The first section of Things I Didn’t Do with This Body is a poignant reflection on the poet’s family. Gunn’s handling of various forms—the sonnets are especially moving—attests to her gifts as a poet. “Girl” is a prose poem about her mother with unexpected, poignant rhymes:

She kept house. And

quiet and small and tenacious as a mouse, she

kept us: three kids, a dog, and a man.

“A Long Ways From Home,” about the speaker’s maternal grandfather, is not about keeping house, but fleeing it:

He wandered far afield, from home to war,

to work, to marriage, out of marriage, gone.

He left the girls his cheerful wife had borne,

still looking for a father, finding none.

As the collection progresses, family members are each given their due. “Happy and Well” is about an aunt and uncle’s grief at losing one child after another. The refrain of “My Father Speaks” may well be taken as an ars poetic for the collection as a whole: “Dad, burden me,” Gunn writes. “Burden me with your secret voice.” Gunn’s poetry is unafraid to tell painful and difficult chapters of family and national history, to burden itself with that weight.

The next section listens for the secret voice of a historical figure: Harriet Tubman. These poems have appeared in literary magazines, and it is a treat to see them brought together in one cycle. In “Araminta,” Gunn describes Harriet Tubman’s “will, her fist, her fox, her game, her would-not-yield, / her God, her faith, her uppity, her name.” Gunn’s Tubman is larger than life. In “Thirty-Nine Objects at the Smithsonian” she continues to pile on honorifics: “dark, deadly, dead and alive, / knife-keen and waiting and resolute.” In “Mystic” Tubman is “Araminta—African lady, with eyes that pierce the mist” whereas in “Coda: Refuge,” she is “Quiet and radical and fast. / Fisher of men. Thief. Spy. Most faithless / slave, most faithful sister.” By assigning Harriet Tubman so many epithets, Gunn lionizes her, doing for her what epic poets have done for warriors and demigods. (Gunn’s gift for epithets is apparent in more personal poems, too. “Hysterisisters,” like Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “the mother,” is a prayer-like meditation on childlessness: “He can take this womb. / This brittle, life-torn, Goddess-built flesh, this never-was, / might-have-been locus of rest.”)

Several of the most memorable poems in this book are stream-of-consciousness monologues, in paragraphs with lower-case lettering and minimal punctuation. Grief, depression, and anxiety are communicated through lines that breathlessly cross the page without the conventional spacing and pacing of verse. “Is it OK” (a question also repeatedly posed in “Corona,” a poem from Adrienne Raphel’s Our Dark Academia) is representative: “Did the antidepressants make me worse did the antidepressants make me better enough to make it worth it am I worse am I lost.”

Like Was It for This, Things I Didn’t Do with This Body pairs the familial with the personal. Effective pairings are threaded throughout, sometimes on facing pages (as with “Bad Romance and “Good Romance,” a pair of poems about compulsively reading romance novels); on the same page (“Things I Didn’t Do With This Body & Things I Did,” two paragraphs written in the style of a list poem); even in different sections (“Ordinary Sugar” is about a beloved grandmother’s prowess as a baker, while “Baker” is about the poet’s own efforts in the kitchen). The interplay of personal and collective history works well; instead of vying for pride of place, each informs and magnifies the other. The speaker’s voice is never lost, even as it dips deep into ancestral and national histories; for it is these histories that inform the poet’s own experience.

Our Dark Academia, by Adrienne Raphel, also explores the hinterland between the self and the world—other people, the things we buy, the media we consume. The collection is brash, stylish, and fun to hold; it’s a book to flip through. Inventive formatting and an abundance of wordplay give the collection a zany, DIY feel. There’s an abecedarian poem (“Alphabet of Spies”), a poem organized like a Clue gameboard (“Clue Gallery View”), and even a flow chart (“Road Map”). There’s also a crossword, since Raphel is a cruciverbalist as well as a poet. “Choose Your Archetype” is a fun, listicle-inspired series, and “Quiz” is a multiple-choice quiz that tests your knowledge of the preceding poems, complete with an answer key.

The flourishes might seem gimmicky at first, but they reflect the way the internet relentlessly and incessantly pigeonholes us into personal brands. Raphel pays attention to the various bits of detritus populating our cultural landscape—videos, horoscopes, ads, diets—and how they define us. One of the funniest poems in the collection, “Midnight Calisthenics,” assumes the unrelentingly perky voice of a Peloton ectoplasm named “Chrissie.”

Have you ever tried

A bath bomb? It totally made my morning

I love it when you make time for yourself

Oh my god you have a dog too that is so sweet

Hold it hold it that’s great!

Raphel has a penchant for mimicking internet lingo and catchphrases. “The Strat” is a poem about “the Strategist,” New York Magazine’s popular advertorial vertical, dropping words to make for a breathless digital rhetoric:

The Strat recommends that weighted blanket.

Do you bidet yet? Yay

Yes hi! Ten out of would recommend.

Like Sullivan and Gunn’s collections, Raphel’s is split equally between poems and prose-poetic (or sometimes just prosaic) sections, the longest of which gives the book its title. “Our Dark Academia” is written in the style of a Wikipedia article, complete with footnotes and a table of contents. As Raphel defines it, “Dark academia is academia’s black swan and shadow self . . . it’s how academics want to see themselves, the apotheosis and the parody of who they always already are.” The poem ends with a nod to Wikipedia: “This article about Dark Academia is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it”; in spirit, the poem it is closer akin to The Official Preppy Handbook. Raphel nails the tone of a pseudo-scholarly article, providing a kind of ethnography of elite higher education in the process.

For all its playful humor, Our Dark Academia is alert to the havoc wreaked by the pandemic on our sense of time, and, like Sullivan and Gunn’s collections, it is alert to the entanglements of the self and the world in the wake of the pandemic. In “Best Unisex Names,” Raphel writes:

I love to click

and two to four business days later, nothing that is not there becomes the delay.

Something, that is.

Everything is scrambled in Raphel’s loopy, very much online world: time and space, oneself and the things one buys. The collection attends to missed connections—more than one poem is about misplacing a piece of jewelry—and the small losses and disturbances that result from these missing pieces. Like Was It for This and Things I Didn’t Do With This Body, it also attends to the particularities of womanhood and coming of age.

Their subject matter may differ in seriousness and focus, but in spirit these three collections reflect the jolts of the era we’re living in, a time when grief and mental health are top of mind, where it is increasingly hard to separate the poet’s mind from the world “out there,” where it seems necessary to modulate constantly between the personal and the political, prose and verse. They are some of the strongest poetry collections of the year thus far, offering rays of compassion, insight, and humor in the face of tragedy.

Published on September 12, 2023