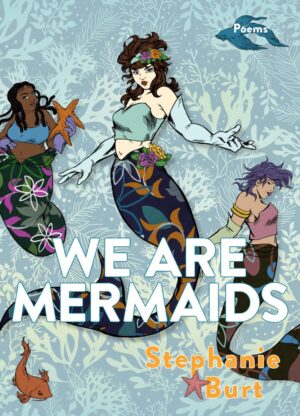

We Are Mermaids

Stephanie Burt

reviewed by Berry Jones

We Are Mermaids, Stephanie Burt’s most recent collection, speaks in the voice of many of her poems, the voice of a thing or things—this could be anything: an airplane, a whale, geysers, flowers, otters, X-Men, sparrows, werewolves—and behind that voice is Stephanie Burt, bouncing herself off her subject.

Burt’s span of interests is at once wide and narrow; her affinity for comics, pop culture, and her own memories returns from earlier projects, such as 2017’s Advice from the Lights, resulting in a collection that sees her continuing to explore herself but stops at what she finds herself appreciating. We Are Mermaids carries a transgender yearning for the unity that identity should bring to one’s self, both past and current.

A professor of English at Harvard College and a former co-editor of poetry at The Nation, Burt is regularly cited as one of the most influential poetry critics of our time and sometimes labeled as a fan. In this collection, she wholeheartedly embraces “fan” as a positive: fan as a point of connection with others in the world, fan as an obligation to speak on the things that move her, fan as a form of gratitude for where she is today.

Burt’s sense of fandom as a place where she has found a community informs her sense of community as a whole. Many of the poems’ speakers use the third person plural, suggesting a community speaking, or an individual within a community speaking as its representative. The metaphor is straightforwardly trans, or at the very least implies a vaguely marginalized community, found in nature or imagination, such as the titular mermaids. The idea may be to lean into the themes of fandom communities, or to fulfill some duty of the trans writer to speak on transness, but the effect is some combination of the two.

Burt’s poems attempt to represent trans people as distinct, but they often end up representing trans people as very much like herself. The poems using “we” follow the same logic as the poems using “I.” “Alison Blaire Explains Herself,” for example, allows Burt to express herself without seeming to speak as a voice for the trans community. In an ode to an X-Men character, Burt channels herself through the elements of Dazzler:

People get into me,

I sometimes think,

Not so much for my voice as for all the glitter

On my belt and sleeves, my dance

Moves, how I swing my hips and hair and see

Into the crowd amid the phosphorescence.

And in “Boeing 757s, Airbus 320s, an Embraer 190,” Burt writes of planes as a kind of community, comparing the imagined culture of planes to trans culture—the power and freedom of flying, the resentment of having to fly within the boundaries and regulations of your passengers:

We were made to do this:

to wait indefinitely,

to make sure we are in tip-top,

polished shape and cleared

of frost and other obstructions

before we take off,

Many trans people find escape from the closet and a sense of belonging in the imaginary and the communities that develop around it. Despite US culture’s relentless and gleeful embrace of escapism generally, escapism for trans people is often criticized. Embracing the unfairness in this, Burt speaks directly from the overlap of transness and fandom, both in defiance and embrace of the stereotype. Perhaps most explicitly, in the poem “Frozen is the Most Trans Movie Ever,” Burt takes the concept of Elsa hiding from the world in shame before embracing her difference-as-strength as Trans Narrative 101.

because it was snowing in our transparent hearts

for 100 minutes or 40 yearsand because the ancient rocks

while well intentioned have big ears

When you are looking for your identity in the world and not seeing it, you settle for what you can get. But while Burt’s intention may be to write for a progressive and like-minded audience of fellow self-identified fans in celebration of their diversity and good politics, the results can sometimes be misrepresentative of the messy lived experience of transness.

We Are Mermaids dips a toe into politics in poems like “Potomac River, 1982,” “Civilization,” and “Whiter.” The latter two, likely written under Trump, mention “our gaslighter in chief” who wants to “indict Lady Liberty,” and feel editorially tacked on to a book that is otherwise not dedicated to political poetry. The standouts, in contrast, are in the poet’s recollections of herself in the nineties, especially “My 1994.” Here Burt’s voice is unobscured by an impulse to be witty or representative, allowing her to reflect with honesty about what identity has shifted for her. Writing “good representation” can all too easily slip into a presumption of what good representation is. Sometimes the best representation is just showing up.

Published on June 9, 2023