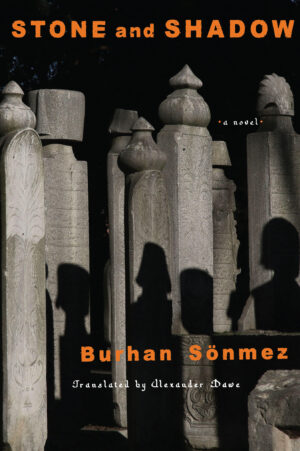

Stone and Shadow

by Burhan Sönmez, translated by Alexander Dawe

reviewed by Wayne Catan

Burhan Sönmez, the novelist and president of PEN International, grew up in Turkey speaking Turkish and Kurdish, and his multiethnic background is apparent in his new multigenerational tragedy. In Stone and Shadow, translated from the Turkish by Alexander Dawe, Sönmez relies on the memory of Avdo, an orphaned gravestone cutter, to immerse us in Turkey’s rich history. Love, sorrow, and violence cut through Stone like Avdo’s chisel through a gravestone.

The novel is delivered in short chapters that span from the 1930s through the 2000s. It begins in an Istanbul cemetery in 1984, where a sickly girl named Reyhan seeks out Avdo, who nurses her back to health. Pregnant and on the run from the police, she relies on Avdo’s kindness to survive. At first, he has no reason to care about Reyhan. But, as luck would have it, Reyhan knows Avdo through her aunt Elif, who is the love of his life.

In the next chapter, we flash back to 1965 and enter a Turkish gazino (night club) where we meet Reyhan’s mother, Perihan Sultan, an Arabesk singer who enraptures the crowd with her syrupy voice and sultry movements. Sönmez has a gift for capturing the unique atmosphere of the gazino. Before her act, “the belly dancer of the night would appear to set the place on fire, shaking her hips and jingling bells on her fingers.”

From here, we drift back and forth through time, learning more about Avdo along the way. Sönmez describes Avdo’s period of homelessness, when he is earning his living singing to his fellow townsfolk before meeting his mentor, Master Josef, who teaches Avdo the art of gravestone cutting. Master Josef is a memorable character, issuing decrees like this one:

In this world we all have a right to a grave, every grave has the right to a gravestone, and every gravestone has the right to a word and motif. The only exceptions are the gravestones of executioners.

Avdo ultimately feels at home in the cemetery, living there for more than twenty years. Although it is an unusual setting for a novel, the author’s ability to bring us into the world of a gravestone cutter is uncanny.

This is because Sönmez truly understands his characters’ predicaments—he was a lawyer in Istanbul before being forced into exile in Britain. Because the author has experienced the violent nature of his homeland—in 1996 he was assaulted by state police—he threads similar passages throughout Stone and Shadow. Sönmez turns his eye not only to state violence, but also to primitive traditions: “In the villages on the plain it was common for children to join old blood feuds from the names that they were given, becoming part of a past they knew nothing about.” Domestic violence is an ongoing issue in present-day Turkey that Sönmez does not shy away from:

I’m not afraid of the dead. I’m afraid of the people in those houses. Sometimes we have such funerals, a brother shoots his brother, a bride is beaten to death by her husband only three months into marriage, a baby is the victim of a bloody feud.

The author’s frustration with violence is further channeled through Avdo and Elif, who are enmeshed in this cycle and culture of violence.

The driving force of the plot is Avdo’s and Reyhan’s fight for survival, their eventual father-daughter relationship, and Avdo’s abiding love for Elif, evident in a song he composes about her:

What if I were to come at dawn to give you a red rose, oh beloved,

A rose lasts as long as a lifetime,

What if I were to say the red of this rose was your blood,

A lifetime lasts as long as a rose.

The book is multifaceted, bringing together folk wisdom, traditions, and song. Sönmez is equally committed to weaving in historical passages, so he flashes back four hundred years, situating us in a time when “the Ottoman Empire was ramping up [its] policy of eradication that it deployed against the [marginalized] Alevi tribes who dwelled in central Anatolia.” He makes sure that readers understand that the peaceful Alevi people were victimized by the Ottomans. However, the issue with these historical sections is that they deviate too far from the plot, forcing us to reread previous chapters before moving on. They are better suited for endnotes.

Stone and Shadow is an epic tale featuring a chorus of voices made up of the dead and the living. Sönmez’s ability to create marginalized, realistic characters who are pulled into the vortex of deep-rooted, unforgiving tradition is admirable. His willingness to reveal the truth about Turkey’s past and present makes Sönmez one of the most formidable Kurdish authors at work today.

Published on August 1, 2023