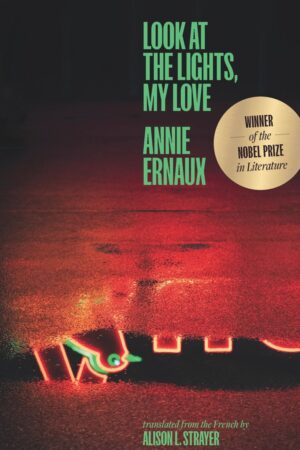

Look at the Lights, My Love

by Annie Ernaux, translated by Alison L. Strayer

reviewed by Marisa Wright

Resigned complicity is the dominant mood of Annie Ernaux’s newest work of nonfiction, Look at the Lights, My Love. Published in France in 2014, the book is a personal examination of the quintessential symbol of modern consumer culture: the big-box store.

Ernaux, who was awarded the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature and is celebrated for the unique way she “turns memory into art” through a disciplined journaling practice, is best known for books like The Years, Getting Lost, and Happening, all edited compilations of her diary entries on themes of gender, language, and class. Look at the Lights, My Love follows in this tradition. The bulk of the hundred-page book consists of journal entries detailing Ernaux’s perceptive observations about superstores and what it means to live in a consumerist society.

Ernaux sets out with a decidedly optimistic tone. Explaining her choice of subject, she writes that big-box stores are central to modern social life, a source of “entertainment or escape from loneliness.” She praises their pluralism: “There is no other space, public or private, where so many individuals so different in terms of age, income, education, geographic and ethnic background, and personal style, move about and rub shoulders with each other … where each has a chance to catch a glimpse of others’ way of living and being.”

The journal entries span from November 2012 to October 2013. In the first entry, Ernaux feels “a rush of pleasure” at the prospect of visiting her local supercenter and maintains an eager, if somewhat muted, desire to return for most of the book. By the end, however, Ernaux grows so disgusted with the superstore that she vows never to return, going so far as to cut up her customer loyalty card to avoid temptation.

Her change of heart reveals a great deal about the role superstores—and, by extension, corporations, and unfettered capitalism—play in our lives. Ernaux’s scrutiny shows the sinister nature of the big-box store as a microcosm of the surveillance state. In her account, a sign hanging above the bulk section warns customers against in-store consumption and that the weight of their items may be monitored at checkout. Seconds after taking a picture of the sign, a security guard appears to scold her. Each time she leaves, her receipt is checked against the items in her cart, and when she doesn’t buy anything, she must use a “no-purchase exit,” which is, of course, watched over by a security guard. Ernaux writes that the store’s video surveillance signs protect merchandise through a “system of incessantly monitored freedom, by internalized fear.”

Her journal entries also catalog a series of revealing observations about big-box stores, from the way they perpetuate existing hierarchies of gender and class to the way they carefully foster a constant desire for more. There are, however, a handful of departures in which Ernaux reports a series of catastrophes in developing countries wrought by mass consumerism. Written in bare prose, the first such entry notes a fire that destroyed a Bangladeshi textile factory, where workers, mostly women, earned just €29.50 per month. “The workers were trapped inside, unable to escape,” she writes. Two other entries describe building collapses that together killed more than 1,300 garment workers who manufactured clothing for Western brands.

Going beyond her personal experiences, Ernaux forces the reader to grapple with the ugly side of an economy designed to give us whatever we want, whenever we want it, no matter the human and environmental cost. Yet Ernaux’s tone is not meant to preach or shame. Nor does she provide simplistic or moralistic conclusions about big-box stores. Even as she boycotts her local supercenter, Ernaux doesn’t dismiss them altogether. In a society with crumbling social infrastructure and dilapidated institutions, she recognizes that big-box stores, for all their destruction, serve a purpose. “Upon leaving the superstore, I was often overwhelmed by a sense of helplessness and injustice,” she writes. “But for all that, I have not ceased to feel the appeal of the place and the community life, subtle and specific, that exists there.”

Like most of Ernaux’s oeuvre, Look at the Lights, My Love is a social commentary crystallized through her own experiences. Despite taking on just one sliver of mass consumerism, she makes clear the disturbing effects of late-stage capitalism, not just on society but also on the individual. Near the end of the book, Ernaux writes of standing in a never-ending line when a question occurs to her: “Why don’t we revolt?”

Because, she later concludes, “We are a community of desires, not of action.”

Published on July 4, 2023