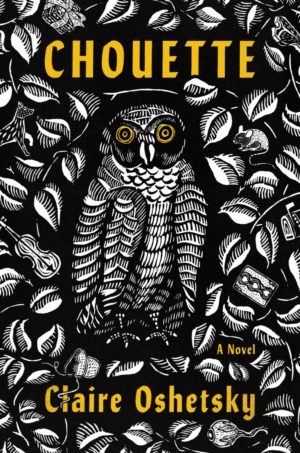

Chouette

by Claire Oshetsky

reviewed by Jennifer Kurdyla

If men are from Mars and women are from Venus, then Claire Oshetsky’s delightfully disturbing novel, Chouette, offers a nonplanetary paradigm through which to view the female experience: the bestial. Equal parts magical realist and radical feminist, the novel follows the plight of Tiny, a woman whose journey through pregnancy and motherhood vies with the most dramatic of Hollywood depictions. For Tiny is not with child per se—not a human child, but rather an owlet, the offspring of an affair she has with a wild female owl in a dream. Through her experience we see motherhood and associated notions of sacrifice, compassion, and belonging upended and redefined.

Right away, Oshetsky asks us to suspend our disbelief. From the very first line, we know we’re in an unreal reality, yet Tiny’s question to her unborn child—”How could such a thing come to pass between woman and owl?”—echoes with a sense of wonder and possibility. A professional musician, Tiny is attuned to the fact that the creature gestating inside her can’t possibly be human. Not only does the baby seem to direct her thoughts, behaviors, and speech, as well as render her body ripe with the smell of rotting meat, but at a rehearsal the baby “hijacks [her] fingers” until she concedes and plays a piece the baby approves of.

After realizing that her career will need to be put on hold for some time—she can’t risk performing, plus her stench makes being in public a challenge—Tiny becomes totally consumed by caring for the owlet. Rather than butterfly-like kicks, she’s beset with wing flaps against her organs. Despite her explicit explanation of what’s going on, her husband maintains that it’s the hormones talking, patting her on the head and keeping her at arm’s reach. She enters her new role alone, making the second-person address of the baby as “you” an intimate invitation to the reader to imagine what it’s like to be at once terrified and assured of one’s future.

Once the baby arrives, Tiny’s world transforms yet again. During the birth itself, she dreams of her owl-lover giving her the ultimatum of a lifetime: “She needs a mother, or she needs to die.” Choosing the former, Tiny conveys a mix of insistence and wariness about her choice to mother the baby, whom she names Chouette, the feminine noun for “owl” in French. With each new obstacle—creating a space big enough for her to molt and learn to fly; supplying her with enough fresh meat to learn to hunt and be adequately nourished (breast-feeding doesn’t work out so well)—Tiny loses more of her human self in service of her offspring. She pushes back against her husband’s insistence that Chouette (whom he calls Charlotte) needs medical attention for her abnormalities, creating even more of a rift between them.

The biggest loss comes when, like all children, Chouette leaves the nest. “What a tiny, stupid life I’ve led!” Tiny cries into the woods her daughter flies off into. “I gave up everything for you! … For nothing! I’m all alone! … there’s nothing left of me but a bitter old woman, one whose rage by now had curdled and warped into a feeling far worse than rage: a hollow feeling, dead-heart, grief-shattered, and bottomless.”

What Chouette explores through its magical realism is the very real unleashing of an animal being that happens in women, especially when they become mothers. The novel asks us to consider why and how this animalistic side—the cravings, feelings, and all-consuming desire to protect one’s young—is taboo. Ask anyone who’s been pregnant, and likely they’d say they, too, were consumed by a non-human being for nine months (and beyond), and that they lost a sense of who they were in the process of watching someone who was once part of them become their own person.

Tiny’s resilience while nurturing Chouette points to a fierceness even greater than the beast she births as she meets her baby’s needs and as she reclaims her own life once Chouette flies away. By the end of the novel, Tiny is more solidly split between animal and human and seems poised to take on anything—including her love for the owl that impregnated her, the most radical element of this radical novel that gave rise to a love that transcends gender, time, and species.

Published on April 11, 2023