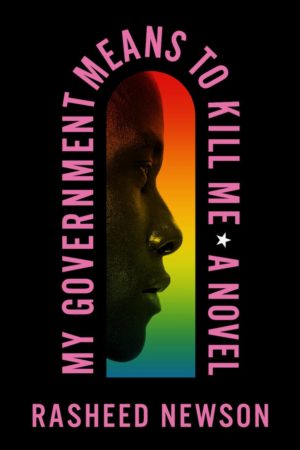

My Government Means to Kill Me

by Rasheed Newson

reviewed by Liza Wemakor

My Government Means to Kill Me marries the radical sentimentality of Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues with the jarring odyssey of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. It may take some time to acclimate to the novel’s steady stream of informational footnotes, which generally gloss the characters who represent real-life public figures, but the trials and feats of the fictional protagonist and narrator known as Trey Singleton will soon engross a reader. The novel’s chapters are organized into chronological “lessons” that establish it not only as a bildungsroman set in the late 1980s, but also as a playbook for survival as a politically conscious, black, and queer man in a country that means him harm.

Through birth and circumstance, teenage Trey lives at the crossroads of the Civil Rights and Gay Rights eras. His parents are wealthy former Black Panthers whose politics have simmered into careers as a speechwriter and policy advisor (his mother) and a pharmaceutical lobbyist (his father). Stringently concerned with the image their family projects, Trey’s parents are not fond of his apparent gayness and evident effeminacy; in addition, they hold a grudge against him for his involvement in his younger brother’s disappearance. Ready to live beyond their scrutiny, Trey leaves his family’s mansion at the age of seventeen—before he’s graduated high school—to make a name for himself in New York City’s bohemia. Trey’s savings don’t last for long, and he suspects that his family is surveilling him from afar, but he does achieve independence, with all the precarity that entails. By the time he’s eighteen, he’s well on his way to becoming a scrappy activist in his parents’ former stead. His primary cause is HIV–AIDs activism, and he achieves prominence as a founding member of ACT UP.

Some of the best scenes in this novel are set in Mt. Morris, a defunct bathhouse that was once a haven for gay black men in Harlem. Trey experiences it as a shadowy set of corridors, replete with private and open sex rooms, locker rooms, and revealing bath towels. His descriptions of the site are immersive, albeit concerning given his relative youth and vulnerability:

[ … ] the reality inside Mt. Morris was stark and graphic: men were having sex with men, often in the open, frequently in groups, and almost never with a condom. To me, it was invigorating. The crowd consisted predominately of closeted or low-key, butch, working-class Black guys. My type at the time.

And:

Now, being stalked into a dark corner of a bathhouse maze and submitting to the carnal demands of an aggressive man that you’ve never spoken to might seem like a strange substitute for the teenage mating rituals I missed out on, but it had raw drama every inch as thrilling as schoolyard puppy love. This was my scene.

And:

Mt. Morris wasn’t only about sex. Over time, I made friends with bathhouse employees and some of the other regulars.

It’s in Mt. Morris that Trey comes into himself sexually, socially, and politically, alternating between cruising for sex partners and seeking the tutelage of real-life Civil Rights organizer and alleged CIA informant Bayard Rustin. (A footnote clarifies that “there is no evidence that Bayard Rustin [1912–1987] was a customer at the Mt. Morris Baths or any other gay bathhouse or sex club.”) A platonic will-they-or-won’t-they tension brews between Rustin and Trey, while Trey embraces an insistently gay and black politic that Rustin shied away from in his own lifetime. Their conflicts reveal the limitations of relying solely on legal systems, particularly the American legal system, to achieve widespread liberation.

Though the novel’s footnotes might make a reader apprehensive, they are increasingly amusing, particularly those that provide tidbits about conservative politicians of the time who were rumored to solicit gay men for sex. These politicians and powerbrokers are principally introduced through Trey’s sex-worker roommate, Gregory, who entertains rich, closeted men in exchange for luxury and excitement. Gregory acts as a surrogate brother and best friend to Trey throughout the novel, protecting him from some of New York City’s harsher realities. Their relationship is touching, comedic, and at times saddening.

If you’re looking for a novel that teaches and captivates through historically-grounded characters, relationships, events, and settings, I highly recommend My Government Means to Kill Me. Newson, who has written for television shows and is one of the showrunners of the drama series Bel-Air, makes good use of his storytelling skills in this episodic, well-researched, and finely written debut novel. Newson’s writing reenacts a moment in time I didn’t live through but feel intimately connected to thanks to his immersive world-building.

Published on October 25, 2022