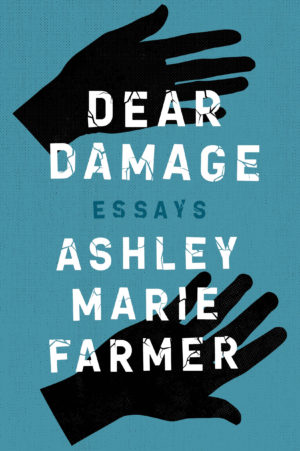

Dear Damage

by Ashley Marie Farmer

reviewed by Laura Albritton

Not all books earn their titles, but Ashley Marie Farmer’s Dear Damage most definitely does. Within the first paragraph of this essay collection, we learn of the “damage” that grips the author and her family: one day, her beloved grandfather Bill “walked into my grandmother Frances’s hospital room with a loaded gun he’d purchased that morning,” killed his wife, and attempted—but failed—to kill himself. Farmer announces that “this isn’t a story I often share,” due to the effect it has on her listeners; she says that “if there’s one thing I don’t want to do, it’s contribute more pain to the world.” However, writing about damage and pain is clearly different from talking about them. Farmer’s straightforward prose (which appears effortless, like most prose that has been carefully honed) invites the reader into her confidence. We realize that in addition to revealing familial trauma, in this book she will attempt to make sense of it—and, perhaps more ambitiously, to make sense of the sacrifice, love, and work that come before and after such trauma.

In “Mercy,” Farmer explains the backstory to her grandfather’s act: following a freak fall, Frances had become quadriplegic and endured incessant pain that would not respond to treatment. Her case was hopeless and seemed equivalent to a sentence of perpetual torture. She repeatedly stated, “I want to die.” Bill, who loved Frances for sixty-three years, thus commits what some may call a “mercy killing.” With such context, one might expect Dear Damage to offer long discourses on the issue of euthanasia, its morality, and how other people have engaged in this practice. Instead, however, Farmer uses her grandparents and their story as a connecting thread in a memoiristic collection focused on many forms of damage and love.

She plumbs several—often intimate—subjects, such as her first marriage, her divorce, her second marriage, gun violence, body image, her discovery of writing, pursuit of an MFA, and her work as an adjunct faculty member. Among all these serious topics, the adjunct material is particularly affecting (especially if one has ever worked as an adjunct). In “American Dream Job,” Farmer successfully conveys the sometimes-overwhelming anxiety that accompanies this unstable form of employment: “zero security from one month to the next, zero benefits, zero prospects.” She fantasizes about working at Trader Joe’s. Her disclosures about living on the fringes of academia are bravely honest: “Docile and sometimes ashamed [ … ] some of us won’t even divulge our tenuous status to our students.”

The structure of the individual essays vary, from more-conventional pieces with standard paragraphing to essays comprised entirely of dialogue, as a film script or a play would be. In some cases, the dialogue is between Farmer and her grandparents, and it’s not entirely clear whether these scripts are remembered or imagined. Regardless, they add a haunting quality to the book, even when the questions are ordinary: “What was your favorite beach?” and “Do you know what street you lived on?” Her grandparents, now both dead, seemingly return to speak to her, and by extension, to us. These script-like conversations humanize Frances and Bill, although the more conventional essays do that as well, often with everyday details and recollections. “My grandparents ditched Los Angeles in the 1970s,” Farmer writes, “when, long after the streetcars and orange groves vanished, the pace overwhelmed them.” Early on, we understand that neither grandparent was a monster or a hapless victim.

As one might expect with a collection of personal essays, Dear Damage does not always feel tightly cohesive. These memories are united, however, by the author’s lens. Farmer’s own life struggles and experiences, some of them routine, still strike one as powerful beside the more dramatic events she chronicles. For example, in “No One is Waiting,” an essay remembering her birthday during the pandemic, she spies a delivery person who moves a snail to safety, to prevent it from being crushed: “That moment of tenderness—this very minor mercy—seems to mean something on a day that is both melancholy and surreal.” Farmer does not attempt to tie up her collection with comforting platitudes. “Certainty is a daydream,” she wisely writes. In the spring, tulips surprise her by blooming outside her new home. Who planted them, she wonders. In a comment that may relate to lost loved ones as much as to flowers, she muses, “Maybe they were just a one-time phenomenon—something beautiful that arrived, made their brief impression, and then disappeared. It’s enough that they were here.”

Published on August 11, 2022