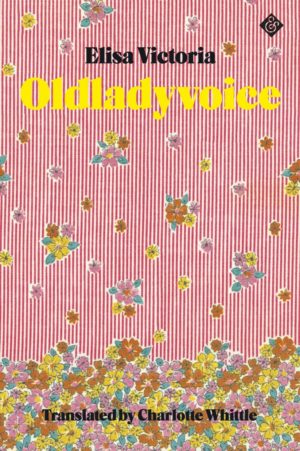

Oldladyvoice

by Elisa Victoria, translated by Charlotte Whittle

reviewed by Gabriella Martin

One of the first images in Spanish writer Elisa Victoria’s Oldladyvoice is of a grandmother sitting on the toilet late at night, leisurely shitting, while her nine-year-old granddaughter, Marina—the novel’s narrator and protagonist—sits at her feet in utter rapture. It’s summer 1993, and Marina is living with her grandmother while her mother undergoes treatment for a serious, unspecified illness that casts Marina’s future in uncertainty. She’s having a great time with her grandmother, who is essentially her best friend, but life is also complicated and puberty looms ever near. Amid the tumult, Marina delights in the forbidden, the taboo, the abject—in shitting and farting, in violence and gore, and, especially, in fucking (or, for now, just the idea of it).

Oldladyvoice, in Charlotte Whittle’s translation, grants us unfiltered access to Marina’s insightful, filthy, amusing internal commentary. The result is a detailed snapshot of the absolute indignity of prepubescence. Marina is desperately, capaciously curious about the adult world’s pleasures and perversions, and frustrated with how far away it all seems. She’s too young for some things and too old for others. She still plays with Barbies, but arranges them in voyeuristic threesomes: “I move his hand toward her flat, hard pussy, outside her clothes [ … ] The third doll has been spying on them from behind the arm of the chair with her leg in a cast.” Her dolls serve as proxies for her to live out her adult fantasies, both in terms of sexual behavior and as a testing ground for new modes of expression: “Even though my dolls say fuck every day, we kids just say doing it.” After making plans to meet with a new friend for a play date, she comments, “I hope it’s this easy to arrange a fuck when I’m older.”

This entanglement of childhood and adulthood is often expressed through Marina’s language, with adult themes discussed in childish terms, like when she reflects that her friend “has fewer hairs on her coochie than me, and this is somehow surprising.” Whittle’s translation captures the push-and-pull of growing up, leaving Marina’s voice playfully recast in English. The overlap of youth and maturity produces a persistent sense of disorientation in the reader, but also one of remembrance, of recognition, of having thought similar thoughts or wondered at the body’s marvels in the same way years ago. It prompts us to revisit our own former selves and to reconsider the depth of children’s experiences.

While the novel paints a portrait of what it meant to grow up in 1990s Spain, also included in this portrayal is a glimpse of what it meant to grow old at the same time. Marina’s grandmother often mirrors Marina’s own state, as their respective ages position them at the margins of society; from there, they find common ground. In a television program they watch together while on vacation, “The panelists discuss things like passion, affairs, and seduction strategies, and the debate is soon full of sexual content. Since I’m with Grandma it doesn’t matter a bit, we’re living our lives so far from the world of flesh we’re immune to it.” However, neither character is a stranger to desire. The grandmother openly lusts after Felipe González, Spain’s then-newly-elected prime minister, and Marina’s fascination with sex is boundless.

Amid this boundless fascination—and at the core of the novel—is a refreshing and total lack of shame. In Marina’s mind, shame around sex or bodies is incomprehensible, yet another mystery of the adult world. When debating whether she needs to start wearing bikini tops on the beach, she comments, “What makes me mad is that I’m supposed to be ashamed when I think the shame has more to do with other people.” She is equally critical of unfounded socialized gender divisions among children: “It’s not like I haven’t noticed how [boys] stare at our dolls and want to get closer.” In this absence of shame lie Victoria’s and Whittle’s talents as storytellers; Marina censors nothing, and so narrates an acutely honest portrayal of the things we do daily in the comfort of our own homes: her grandmother’s toilet rituals, for example, or Marina inspecting her vulva in the mirror while her grandmother naps. And not only is there no shame, but there is no male gaze here, either—Marina’s “only inheritance comes from women.”

At one point, Marina laments that adults seem to not remember what it felt like to grow up, what it felt like to be nine years old. Exasperated, she asks, “But what’s up with that, Mom, how come so many people seem like they don’t remember anything? When do they forget?” The curiosity about sex, the titillation derived from the forbidden, the confusion, the frustrations—didn’t you feel all of that, too? Or had you forgotten?

Published on November 2, 2021