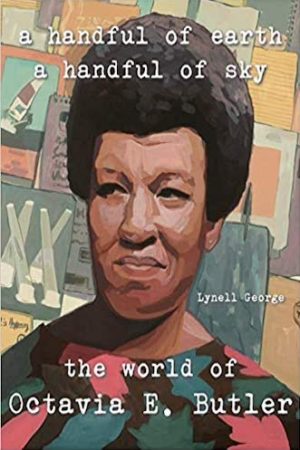

A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky

by Lynell George

reviewed by Smaran Dayal

Octavia Butler was a California novelist. The countless op-eds, articles, and “listicles” that have begun to appear with ever-greater frequency over the past decade about Butler and her work sometimes mention this fact, but it’s rarely explored in any depth. Lynell George’s A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia E. Butler is arguably the first work of writing to give this dimension of Butler’s life—its geographic placement in the world of southern California—sustained attention and descriptive heft.

Like any writer, Butler was profoundly shaped by the circumstances and setting of her life: material, geographic, psychic, and historical. However, because she was a profoundly private and introverted person, only a limited amount was known about her personal life until the recent wave of work that has emerged from her literary archive, the Butler Papers, at the Huntington Library. Gerry Canavan’s 2016 book-length study of her fiction and archival papers, Octavia E. Butler, was transformative for the fresh perspective it offered into Butler’s writing process, her tireless self-editing and revisions, and the political context that gave birth to some of her stories and characters. We now know, for instance, that President Jarret in her Parables novels was inspired by Reagan and Hitler. Likewise, Butler Papers curator Natalie Russell’s recent article in Women’s Studies offers a rare insight into Russell’s compilation and organization of the archive.

A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky, which similarly emerges from George’s research in the Butler Papers over four long years, approaches the archive in a very different way, offering a unique angle on Butler’s writerly method, as well as her personal and inner life. George writes that she “wanted the book to mimic the rush of moving through the archive itself.” With the ample photographs, interspersed diary entries, notes, letters, library call slips, and other scraps of writing, George’s book comes closest to what I imagine is the actual experience of slowly working through Butler’s archive.

The result is a stark picture of a writer struggling against unbelievable odds to realize her stated dream of becoming a successful author of science fiction. For so much of her life, we see, Butler teetered on the precipice of financial ruin, an existential anxiety that was compounded by a series of rejections and scant external validation in the early decades of her career. Watching Butler’s uphill battle to earn a living as a writer through the traces of her archive is gut-wrenching, to say the least. But what George foregrounds alongside this struggle is Butler’s “dedication,” her “single-minded pursuit” of a writing career, her enabling “rituals” and “obsessions,” and most of all, the “labor” that went into becoming the writer that she was. One of her many notes to herself reads: “We must become a writer—one who writes for a living. As well as a way of life.”

George successively details the different aspects of Butler’s method: all the tools, implements, psychological habits, sources of inspiration, sites of research, and plain and simple Sitzfleisch that went into Butler’s intentional construction of her life as a writer. These range from her omnipresent notebook, meticulously calibrated daily schedule, calendar, and various methods of self-care, discipline, and motivation to the crucial public resources like the LA Public Library and Metro bus system that enabled her work. (Butler famously never drove, even though she lived in a city notorious for its dependence on cars.)

When she wasn’t taking the bus to her current part-time job—Butler worked the whole gamut of waged positions, “minor clerical, factory, warehouse, laundry … food preparation”—or reading and researching her novels at the Central Library in downtown LA, Butler could be found walking the hills and foothills of the San Gabriel mountains (“my mountains,” she called them) not far from any of her various homes in North Pasadena. We see the San Gabriel Valley landscape rendered in vivid detail in her novel Parable of the Sower (1993) as her characters trek north across a post-apocalyptic United States. In fact, a handful of her novels are set, partially or entirely, in California. And most of Butler’s protagonists were, like her, Black women from southern California: Dana from Kindred, Lauren from the Parables, Lilith in Xenogenesis, Mary in Mind of My Mind.

What’s uncanny and compelling about A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky, and by extension the Butler Papers themselves, is that you aren’t entirely sure you should be allowed such extensive access to the inner life of a person who intentionally stayed out of the public eye. But having her papers archived at the Huntington was Butler’s decision, and her primary reason for doing so, George suggests, was to provide a roadmap for others: “When she was saving and securing the quotidian scraps … I’m sure she wasn’t thinking so much about legacy as she was about leaving documentation for her toil here, a sense of how it’s done and what it takes—time, effort, sweat.” George has done aspiring writers an immense service by making the road map and method contained in Butler’s papers accessible through this beautiful book.

Published on May 21, 2021