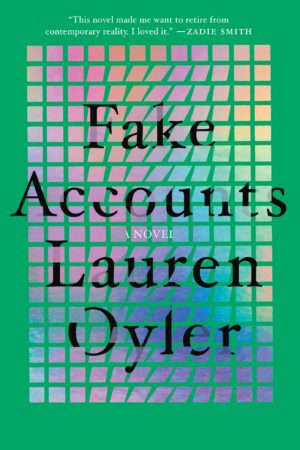

Fake Accounts

by Lauren Oyler

reviewed by Teddy Burnette

With her debut novel Fake Accounts, Lauren Oyler—best known for her work as a ghostwriter, essayist, and sometimes scathing critic of popular books (her critiques of popular works have become something of a calling card)—writes an incredibly readable book, especially when the narrative is allowed to take over and move away from clever remarks and asides.

Fake Accounts begins with the election of Donald Trump, but quickly shifts focus to the unnamed narrator’s relationship with Felix, her current boyfriend, and the secrets he may or may not be hiding on his phone. They first meet in Berlin on a bar crawl—Felix is the tour guide—before he moves to New York City to live near her and work at a startup. Then there’s the first big reveal: Felix runs an Instagram account propounding wild conspiracies to a captive audience of followers. The heart of the novel begins with this discovery.

The unnamed narrator seems to be modeled, in part, on Oyler: she has lived in Berlin, she wrote at a blog, and there, like the “retrograde cynic” narrator, developed her voice. After attending the Women’s March on Washington, DC, and contending with modern-day issues like policing, whiteness, and the effects that protests can have, the narrator plans to break up with Felix once and for all.

Interspersed in between these episodes are questions and admissions directed at the reader. The narrator makes amends for her privilege, or at least acknowledges it. She sporadically refers to a group of ex-boyfriends who pop up like a Greek chorus—or possibly more like a reality show audience, oohing and aahing and occasionally booing their favorite character’s actions. When Felix’s mother calls to inform the narrator that he has died in an accident while riding his bike, she has the cynical response we’ve come to expect of her: she realizes she does not have to break with up him anymore.

Many of the themes in this novel, especially following the narrator’s move to Berlin after Felix’s death, center on social media. Not to be too on the nose, but it’s about the fake accounts and the fake lives people create. The novel is beset with anxieties about social media: how it glamorizes moving to a new country at the drop of a hat; how our community on the Internet—even if we’re not aware of having one—is lost when we move to a new time zone. The narrator’s time in Germany is recounted through her dating life, which allows for long-winded explanations of the pros and cons of Tinder and other apps. In one of its slower portions, the novel is organized—seemingly for the sake of doing so—around the narrator’s attempt to date a man of each zodiac sign. (Oyler concludes this section with, “The ex-boyfriends mean this in the most loving way, but they’re feeling like they really dodged a bullet here.”)

The final reveal of the novel again concerns Felix, who, despite being the only character in the book who does not talk incessantly about himself, is the clear driving force behind the story. Just like the narrator, he too lies. Very little that’s said can be believed in this novel, which may be on purpose. In an age of instant access not only to information but also to the private lives of those around us, believability, Oyler suggests, might not be the point anymore. At no point are Felix and the narrator forthcoming with each other about the true facts of their lives. The only mention of a person leading a life with the actual facts of their past and personality comes late in the book, when the narrator describes an acquaintance named Nell: “She believed she had defined personal qualities and preferences and she used them as a foundation to think whatever she wanted, especially if what she wanted to think was whatever she was told.”

For better or worse, evasiveness drives each character’s story arc. Oyler adheres to the theme of fake lives and the stories we tell about ourselves, but the reasons behind these fake accounts—why they’re used or even created—seem empty. As a result, much of the book feels overly cynical. As Oyler herself writes: “At some point you have to admit that doing things ironically can have very straightforward consequences.”

Published on February 26, 2021