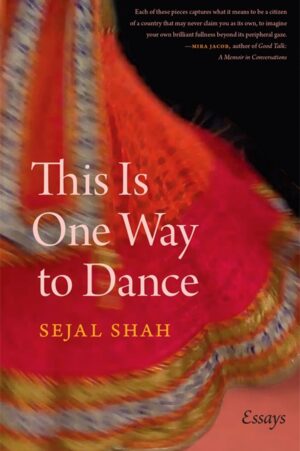

This Is One Way to Dance

by Sejal Shah

reviewed by Rajpreet Heir

Sejal Shah’s debut essay collection, This Is One Way to Dance, is an examination of the hypervisibility and invisibility of South Asian Americans. In twenty-five linked essays written over two decades, Shah reflects on experiences from her own life and explores a range of subjects including weddings, representation, intersectionality, place, race, pop culture, and identity. The daughter of Gujarati immigrants from India and Kenya, Shah grew up in western New York, where she still lives. In her essays, she traces time spent in her mostly white hometown and its small Indian community, her graduate school years in New England, time spent teaching in Iowa, and her trips to Italy and France. She explores what it means to be Indian in non-Indian places.

The collection begins with an introduction, in which Shah explains the title of the book: “I don’t subscribe to the notion of fixed genres—not when I and others move from one culture to another, from one kind of dance to another [ … ]” Shah’s life and her way of looking at it are her own. She is not speaking on behalf of all South Asian Americans; she does not want you to use her story to simplify a whole group’s experiences. This book is about pushing boundaries, both of stereotypes and of form. The essays follow Shah’s progression as a writer—from poet to prose enthusiast—and her genre-bending collection mirrors the way she rejects the confines people place on her. Her creative range arises in part from her layered background and from the agility she developed in response to the ignorance of others when confronted with that background.

“Matrimonials” centers on the lack of representation of South Asian Americans in mainstream American culture. It’s still lackluster now, but it was even worse in 1992, when Shah attended her brother’s wedding, held in a hotel. It was one of the happiest days of her life because, at the age of twenty, it was the first time she saw her Indian and American cultures merge in a semipublic space. At that time, there weren’t any South Asian Americans on prime-time television except Apu, the Kwik-E-Mart manager on The Simpsons, whose exaggerated Indian accent was voiced by a white actor named Hank. Bollywood hadn’t yet made it over to the US in a significant way, and Shah hardly saw Indians represented in American pop culture, nor were they in The New Yorker or other visible and prestigious places. At her brother’s wedding, by contrast, Indians weren’t in the background. Instead, “to catch all of the references, you had to be Indian, you had to be Indian American—you had to be us.”

Weddings of friends and family friends served as a refuge for Shah during her graduate school years in New England, where nearly everyone was white. In the lyric essay “Skin,” she says the problem with western Massachusetts is that “you are a brown girl here, never just a girl.” Shah constantly felt aware of her Indianness not only in her in her social life (in “Who’s Indian?” she recalls the familiar experience of a guy at a bar refusing to accept that she’s from New York), but also in her writing career. Not seeing people who looked like her in publishing made Shah doubt whether she should send her work to editors. In “There is No Mike Here” she references a time when her cousin suggests she submit an essay to Granta and she wonders: “Who was I to submit to Granta?” Shah confronts limits she has created for herself as well as those that have been created for her by others.

In “Betsy, Tacy, Sejal, Tib,” Shah makes a brief venture into fiction to push against our established idea of young adult literature. She shares that her longing to see her experiences reflected begin when she was young and reading American girlhood classics, Sweet Valley High and Nancy Drew, in the 1980s. Then she provides us with an imagined excerpt of the literature she wishes she’d had: “In each other’s houses, they could relax. No explanations were necessary about why their mothers did or did not wear saris, about what that dot meant (how were they supposed to know?), about the difference between Hindu and Hindi, about why their parents were stricter than American parents, about why they always took their shoes off in the house.” This essay is brilliantly economical: Shah shows us what it was like growing up in a segregated town, demonstrates the contrast between her daily life and the ones normalized in American literature, and allows us to experience work that would fill out the larger literary landscape.

Through incorporating poetry and fiction, moving from place to place, and switching among first, second and third points of view, Shah has produced a work as original and distinctive as she is. She explains that she “began writing to make a point of view, people, and entire cultural references I never saw reflected in what I read or watched,” and she achieves this. She shows what’s possible when we don’t subscribe to personal or creative restrictions.

Published on July 14, 2020