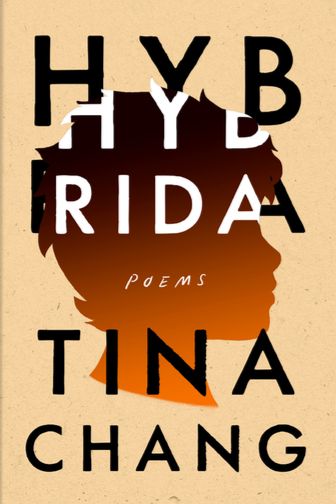

Hybrida

by Tina Chang

reviewed by Carly Rubin

With its poems of motherhood, of childhood, of race and difference, of being and loving, and of the body, Tina Chang’s Hybrida offers readers plenty to hold on to. This is Chang’s third full-length collection, following Half-Lit Houses (2004) and Of Gods and Strangers (2011). In each, Chang, who is the Poet Laureate of Brooklyn, meticulously weaves together history, memory, and the contemporary moment with her lyric forms. Here, Chang writes about her role as a mother of a mixed-race child, about her young son and his blackness, and about many recent tragedies, the deaths of Michael Brown and Leiby Klietzky and the shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church among them. She writes, too, about the longer history of American racial tensions within which these subjects can be contextualized. As she navigates the challenges of raising her son in a country and moment that pose no small threat to him, Chang renders the abstract concrete:

I made dioramas of the future: paper birds rested on live wire,

a sculpture of the sun rose like a mouth, then all the living

ones died magnificently inside the box. After that

there was song. Voices sprang out of the box with coil

and hinge. [ … ]~

I twisted the theory around my ankle like an anchor.

More like an ornament, jewelry I once loved. I wound it

around my leg, my bone loving the tension.

These lines imagine the uncertain future in material terms: as dioramas of paper, wire, hinge, box, metal anchors, jewelry clasped so tightly it presses against bone. At the same time, the solidness of the world Chang crafts is undercut by things harder to grasp—mouths, songs, voices, speech. When the poet wonders if raising her son means she understands “what it means to live as a black boy,” she also asks how she can “speak of his existence without appropriating his existence.” How do we talk about our complicated, entangled experiences? How do we talk about those we love, who must move through the world differently than us? What language can translate the vocabulary of our lives, representing our stories without doing damage by the act of translation? “How can we make sense of chaos? What is the form for that?” wonders the speaker of another poem.

Hybrida is at its core a book of forms—bodily, linguistic, and poetic. Chang brings together poetic structures like the zuihitsu (a Japanese form, like a lyric essay or a collage, composed of vaguely connected fragments, ideas, observations, and personal notes), the ghazal, the prose poem, and the ekphrastic poem. She integrates these structures with visual symbols, dictionary definitions, a hyperlink to a YouTube video, quotations, historical narratives, fairy tales, and images. This collage-like mode makes Hybrida a stunning investigation of what textual form is and what it can do. Take Chang’s use of the ghazal, a short Arabic poetic form dating from the seventh century with roots in an even older Persian poetic tradition and a central place in Urdu poetry traditions. Designed for public performance, a ghazal is composed of couplets, each self-contained, with the exception of refrain words repeated throughout. In some ways, this form is a perfect fit for Chang’s purposes. Traditionally, the ghazal speaks of deep—divine, even—love and devotion, as well as grief and loss. The ghazal is also a form that interrogates the boundary between separation and closeness: each ghazal couplet is grammatically and thematically enclosed, self-sufficient and self-sustaining, but all the couplets must still work together as one poem.

In “Fever Ghazal,” Chang’s speaker questions the relationship between person and place:

Here is a place that was once mine, each grown flower a fever

reaches through a gate, now flourishes like a wounded fever.The body was once a compass leading due North. When it broke

I could say I was lost or free. Each step a hounded fever.When he sleeps, my son is neither broken nor compromised,

his body a road leading to a house of spoon-fed fever.My nation speaks stories into my mouth as if they were mine.

Are they document, aftermath? The news a clouded fever.

Ultimately, Chang uses the self-referential quality of the form (traditionally, an author refers to herself by name or nickname in the final couplet of a ghazal) to add nuance to her vision of identification. Rather than name herself in the poem’s penultimate line, Chang names her nation: “Matches struck by the light of your weary hand, America, / papers burned in the quickening gold, God’s mind crowned in fever.” These formal maneuvers lend a poignant, intimate complexity to the link between a person and their home. By naming America where the ghazal’s form has trained us to expect her own name, Chang complicates the rhetoric of brokenness and harm with one final, tender, connection.

Here, as well as in the extensive musing on the zuihitsu mode in the book’s second section, Chang exhibits her interest in the capacities of different poetic forms to carry both emotional vulnerability and incisive social critique. In “She, As Painter,” the speaker begins by telling us: “I sing a song to my children. / If I sing it just right, it is greater / than a psalm. It is a hilltop. / It is thunder.” The lyric poems of Hybrida are also a kind of singing—and Chang gets them just right.

Published on October 29, 2019