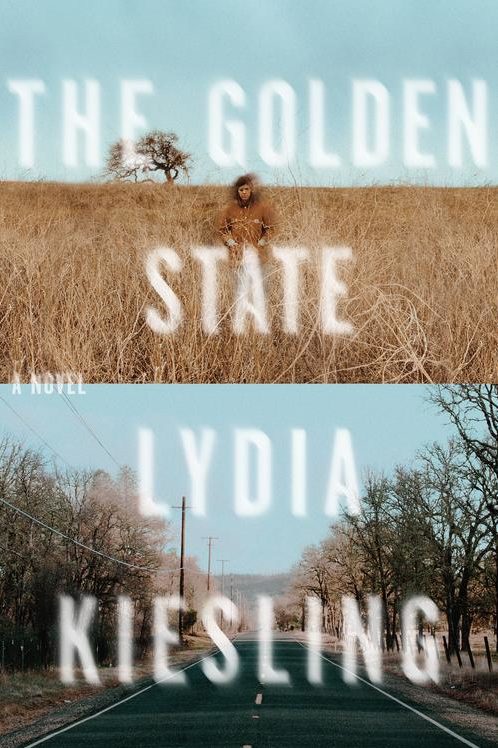

The Golden State

by Lydia Kiesling

reviewed by Walker Rutter-Bowman

The Golden State opens with an epigraph from Philip Larkin: “Home is so sad.” Like Larkin’s poem, Lydia Kiesling’s novel makes this line feel poignant and true rather than sentimental or glib. The novel aims to define a notion of home, to sketch its scope and limitations. Is it a place, a time, a community? What say do we have in where we belong? Such questions are not just poetic or thematic but also deeply political, and Kiesling’s novel explores the politics of belonging.

Daphne lives in San Francisco with her sixteen-month-old daughter, Honey, and works as an academic administrator at the Institute for the Study of Islamic Societies and Civilizations. One morning, a “morning not worse than most mornings,” Daphne, missing the smell of her northern California hometown, and thinking of her daughter at daycare in a “dingy living room where Honey and six other babies spend ten hours a day toddling,” leaves the office, packs the car, picks up her daughter, and drives north. Her call to action is faint, a vague “tugging.” She hopes to reclaim the comforts of home in her grandparents’ house in Altavista, six and a half hours north of the Bay. The house, a “homely beige rectangle with a brown latticed deck and a tidy green wraparound lawn,” is her inheritance, passed from her grandparents to her mother and then to her when her mother died. In the span of ten days, spent in or near the Altavista house, Daphne reckons with past and present, cares for her daughter, and attempts to scrape together enough resolve and hope to face the future.

The plot is refreshingly modest. Daphne schleps Honey around Altavista, testing the toddler’s patience at various dining establishments, leeching Wi-Fi from the local café. Kiesling captures a meticulous mind harried by the stresses of parenthood, work, longing, dread. To represent the tumble of Daphne’s thoughts, she builds long lists of objects and actions, sparing the commas:

It is already 7:15 when I have done a rough inventory of e-mails and Honey will coo any minute so I go inside and wash my hands and slice a banana into very exact half-inch slices and get out two eggs, so many eggs we are eating, too many eggs, and fly around the house picking things up. We didn’t bring very much stuff up here but what we did bring has multiplied in the way of children’s things and there are single socks and stuffed animals I don’t even remember packing and books and the ubiquitous halves of The Very Hungry Caterpillar and the many bibs and wipes I use to wipe her nose which is always runny but which the pediatrician assures me is no cause for concern.

The catalog of detail contains flashes of levity, like Daphne’s pride in those “very exact half-inch slices” of banana or her grim wonder at the “ubiquitous halves of The Very Hungry Caterpillar.” Kiesling allows Daphne to be contradictory, equally full of weathered wisdom (“in the way of children’s things”) and the fresh worry of new motherhood (“which the pediatrician assures me is no cause for concern”). Without a strict sense of portion control, the words overwhelm, but pleasantly so—even when this style is at its most excessive, it’s a pleasure to be among Kiesling’s churn of the itemized: objects, foods, actions, anxieties, and observations.

Alongside Daphne’s vividly portrayed experience of motherhood, the book stakes another large claim to the reader’s feelings: Daphne’s husband, Engin, a Turkish national, cannot return to the United States. While he was trying to reenter the country, Homeland Security officials bullied and coerced him into surrendering his green card; now bureaucratic ineptitude and malice bar his reentry. The National Visa Center admits Engin is the victim of a “click-of-the-mouse error.” Daphne begins to wonder what she’s doing staying in the country. Is staying an act of passive loyalty to a government dividing families with relish? And where is Honey’s home? Her American mother feels out of place; her Turkish father is a distant face on a phone screen, an apparition of spotty café Wi-Fi.

Kiesling’s book examines American whiteness and the ways it can be wielded. With good humor but shades of self-censure, Daphne looks at her own record: “There’s an unspoken competition among American grad students in Middle East and related studies to be the least Orientalist and problematic and obviously by falling in love with a Turk during a hot Istanbul summer I lost this contest fair and square.” Daphne’s white guilt is exacerbated when she sees whiteness applied to ignoble ends, like the white pride of some northern Californians who hope to secede and form a new State of Jefferson. Ostensibly, their gripes are high taxes, public land, and underrepresentation, but these complaints are lipstick on the pig of a more hateful cause: white hegemony. The secessionists fear a rising tide of immigrants and people of color. They would not share their America with Honey and Engin.

In Altavista, Daphne and Honey meet ninety-two-year-old Alice, who is on a mission to visit the camp for conscientious objectors where her husband worked during World War II. When a friendship forms, Daphne offers to take her to the camp, a four-hour drive into Oregon, and they hit the road. Daphne is fascinated by Alice, who, in surviving her husband and children, has endured what Daphne fears most. This final act strains, shoehorning another tragedy into a book already rife with sadness. It does, however, move the novel to a final showdown with the secessionists, and prompts Daphne to make the decision that fittingly concludes the novel. But these larger events pale in comparison to the best work in the novel: the pinhole-specific study of Honey’s eventful present. In one moment, the toddler calls from her crib “like a marooned sailor”; in the next, she brandishes a cheese stick like a “floppy baton.” Daphne’s attention to her daughter reveals Kiesling’s great feat: a voice of stylized immediacy.

Published on July 23, 2019