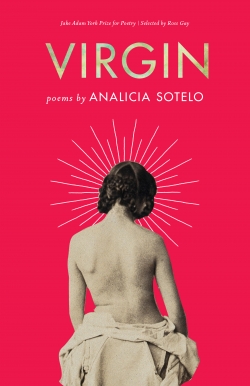

Virgin

by Analicia Sotelo

reviewed by Carly Rubin

“We were really getting down,” writes Analicia Sotelo in Virgin, “dancing hard on the injury.” Sotelo’s poems do just that, with an insistent force that commands attention and dares readers to dance along. Virgin is a declaration: self-aware and self-assured, in control even as—especially as—it contends with the definition of femininity within the social and sexual dynamics of our cultural moment. Ultimately, Sotelo’s poems demand and perform necessary revisions of that definition, reclaiming the concept of femininity and revealing its inherent power. In “Trauma With a Second Chance at Humiliation,” the speaker asserts to a man, “I’ll turn you // into something else, a footnote / of a person.” These lines, in all their authority, reveal one of Virgin’s most essential elements: a woman who owns her own narrative, who is determined to write her history, herself.

The collection is organized into seven sections—“Taste,” “Revelation,” “Humiliation,” “Pastoral,” “Myth,” “Parable,” and “Rest Cure”—which speak to and build off each other but maintain unique, distinguishing qualities that become more powerful as a reader spends more time with the book. “Humiliation,” for example, is filled with poems focused on the subject of personal trauma, while “Pastoral” engages with familial memories. The collection’s first poem, however, remains outside of these sections: “Do You Speak Virgin?” stands alone and acts as an introduction to the language Virgin will use in addressing and repossessing the feminine experience. The opening lines communicate both vulnerability and power, as the scene is set for us:

This wedding is some hell:

a bouquet of cacti wilting in my hand

while my closest friendssit on a bar bench,

stir the sickles in their drinks, smile up at me.

The speaker is in both a position of authority (her friends smile up, figuring her as above them) and exposure (she has been put on display, is being watched by her sickle-wielding audience). There is a clear deadliness at play (the cacti!); the marriage ritual has been reimagined. The poem is composed of declarative sentences; most are uncomplicated syntactically, but all are freighted with meaning. When the speaker announces that “I am a Mexican American fascinator,” for example, we hear both a firm declaration of identity and a confrontation with the pervasive gaze through which women are reduced to accessories, embellishments. “Do You Speak Virgin?” identifies the rhetorical framework underlying the pieces that follow—the husband stays silent, the body does not inspire fear, the real threat is not knowing. This beginning poem promises that what comes next will be revelatory, promises we’ll see “how far & wide, / how dark & deep // this frigid female mind can go.”

One of the most powerful ways in which Sotelo shows us how far a female mind can go is through her adoption and reworking of Ariadne, the mythologized Cretan princess. In the classical canon, Ariadne’s story varies: either she betrays her god-husband for a mortal man and is killed out of revenge, or she is betrayed by her beloved and is rescued by a god who makes her his wife, or she is summoned away from her mortal beloved by a god who wishes to marry her; she herself is variously described as a mortal woman or a goddess. The many versions of her story and the persistently disempowering nature of each one makes Ariadne the perfect figure for Sotelo to reclaim. In poems like “Ariadne Discusses Theseus in Relation to the Minotaur,” “Ariadne’s Guide to Getting a Man,” “Ariadne Plays the Physician,” and “The Ariadne Year,” the princess is given the voice traditionally denied to her, and she knows how to use it, as when she demands that

We must set this story straight.

We must say there is another angleto this foreign particle

lodged in my ribs like a small ivory

tiger or a Chinese lamp, the oilcoating my bones. Theseus,

you know you didn’t break me.

Sotelo reworks familiar rituals and narratives of objectified femininity, and in doing so asks her readers to consider the histories that shape our current struggles. There are also poems in the voices of Theseus and the Minotaur, which reveal as much about the women whose lives they affect (Ariadne, Pasiphae) as they do about their speakers. Virgin is a book of many voices—outside of the mythologies, poems like “My Father and Dalí Do Not Agree” and “My Mother as the Voice of Kahlo” maneuver bodies and speakers, evoking questions of influence and inheritance as they relate to the book’s larger themes.

Virgin is the inaugural winner of the Jake Adam York Prize, and it’s not difficult to see why. Sotelo’s poems are sure of themselves, firmly authoritative and unflinching. “I am not afraid to go back in time, / to have the moon reflected in my big brown eyes / as the terracotta roof arcs its terracotta arches,” Sotelo writes, and this is the attitude of her book as a whole. Virgin, with its insistent questions about femininity and its unyielding demands for a new and better truth, reaches through contemporary life and into the pasts that have shaped it, pulling myths and memories into the present and opening them up to reimagination.

Published on May 29, 2018