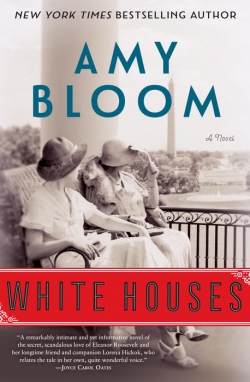

White Houses

by Amy Bloom

reviewed by Laura Albritton

In Amy Bloom’s new novel White Houses, journalist and “First Friend” Lorena Hickok chronicles the vagaries of her love affair with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Bloom developed the book’s premise after coming upon a huge cache of letters written between the two women; judging from descriptions of their content, these letters seem to affirm the romantic and physical nature of the two women’s relationship. Author of several novels, including the National Book Award finalist Come to Me, Bloom deftly plunges the reader into their private world and captures Hickok’s wit from the very first line, as the journalist remarks in language both dry and nostalgic, “No love like old love.”

The prologue starts in 1945, as the two former lovers reunite after Franklin Delano Roosevelt has died. “Hick” (as she is nicknamed) recalls their first, excited declarations of love, when “my ears burned.” Bloom does a marvelous job of approximating Eleanor Roosevelt’s upper-class, effusive manner: “Lorena Alice Hickok, you are the surprise of my life. I love your nerve. I love your laugh … I love your beautiful eyes and your beautiful skin and I will love you till the day I die.” Chapter by chapter, as the book flashes back to Hickok’s youth and to her early romance with Eleanor, then flashes forward to various points in time, Bloom creates epochs, places, and characters that are convincing and engrossing.

Very few readers will have heard of Lorena Hickok. In addition to rendering the story of a romance, Bloom also uncovers the life of an exceptional woman who managed to achieve considerable success despite an impoverished, difficult childhood. The author traces Lorena Hickok’s early years, which included abandonment, sexual abuse, and toil as a “hired girl.” It is only when the adolescent falls in with the circus and works as its secretary that her fortunes change. She bunks with the freaks, who show her kindness; their deformities have made them acute and compassionate observers of human nature. Speaking of their downtrodden audience, the Alligator Girl says, “We’re a comfort, we are. God’s conspicuous errors.” One man who works for the circus gives Hickok enough money to reach an aunt in Chicago, who takes her in. After attending and completing high school, she goes to college on a scholarship and then starts writing for a newspaper.

One can see why Bloom chose Hickok, a fellow writer, to narrate the novel, because writers—like the aforementioned freaks in the circus—also hone their powers of observation. Even as the narrator describes her beloved, she perceives Eleanor Roosevelt’s shortcomings and idiosyncrasies clearly and records them with a literary flair. In one instance, Hick notes that earning Mrs. Roosevelt’s disapproval is “like having the Statue of Liberty watch you have one beer too many. Everyone except Franklin would shrink a little and Eleanor would purse her lips, as if she was so clobbered with disgust, she couldn’t hide it.”

The First Lady invites Hickok to move into the White House; the “First Friend” will live there for years. Bloom sketches an unusual ménage—a White House in which the president seems completely cognizant of his wife’s predilections, and his wife entirely aware of his philandering. The author portrays Eleanor Roosevelt’s love for women, but also her jealousy of FDR’s lovers: an interesting and pleasingly complex rendering of her psychology.

Some of the most captivating passages of the book occur when Hickok describes FDR. While she acknowledges that “History should show him to be a great man, a great leader,” she adds that he is also “a silver-tongued con man and a devil with women, but if it doesn’t show that they adored him, it’s not telling the truth.” She shrewdly recognizes that “They loved him not despite being a cripple but for it … Need is like a handful of salt on the fire for most of us. He was a hell of a man before polio. Polio made him irresistible.”

Although the era required that Lorena Hickok hide her sexual orientation, she seems at peace with her lesbianism. Certainly, Bloom ensures that her character knows that she and Mrs. Roosevelt run the risk of public scandal, yet Hick does not suffer angst or guilt. Instead, we are privy to the warmth of their romance: “We used to say, we’re no beauties, because it was impossible to tell the truth. In bed, we were beauties. We were goddesses. We were the little girls we’d never been: loved, saucy, delighted, and delightful.”

One mystery that Bloom does not solve, at least not fully, is why Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok drift apart and finally agree to live separate lives. There are allusions to falling out of love: “I wasn’t in love with Eleanor. We had agreed that ‘in love’ had burned out after four years for us, the way it does for most of us, in two months or two years and, I guess, never for some lucky people.” Yet living without Mrs. Roosevelt makes Hick feel like an amputee. It is suggested that perhaps the journalist can’t bear to be a White House “pet” or that she cannot stand to share Eleanor with FDR. Either way, none of these suggestions feel entirely convincing; Bloom so thoroughly persuades us of their love and devotion that their breakup remains a puzzle. This is, however, hardly a serious quibble about White Houses, a finely crafted novel that absorbs and enchants at every turn.

Published on May 17, 2018