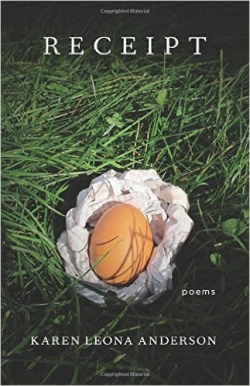

Receipt

by Karen Leona Anderson

reviewed by Julie Swarstad Johnson

When recently asked about the importance of the humanities, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Junot Díaz described our current situation this way:

We’re in a period of rabid privatization […] everything is a site of profit extraction. Given that context, for me, that’s where we’ve got to begin these questions: by sketching out the forces—political, economic, and social—which are distorting our ability to have a reasonable conversation.

Receipt, Karen Leona Anderson’s second collection of poetry, sketches out the forces Díaz indicts, those that distort our conversations and daily lives. In poems that use cookbooks, shopping receipts, and the nonhuman world as starting points, Anderson interrogates the connections between American consumerism, postwar domesticity, and environmental degradation. Against such forces, Anderson asserts, good intentions provide no defense. We see this microcosm in poems such as “Pizza Night,” where good-willed striving toward organic eggs and “kale, local, wilting in on itself” gives way to “needing to feel / full of the worst thing you can / without meaning anything.” Consumer culture’s demand that we buy, buy more, and go into debt—for “weddingdress hospital white-flowered / lawns”—leads the speaker of “Meringue ($3.25 Pâtisserie Belge)” to gasp out amidst added space:

how much more can I be

Receipt doesn’t explicitly argue for another way of being: it immerses us in the failures of our present structures.

Cookbooks provide Anderson material in “Recipe,” Receipt’s opening section. The Can-Opener Cookbook (1951) and the Food Network frame the timeline, with one exception: “Gingerbread” riffs on American Cookery (1796) and its author who “knows how to find // a man: a contract: a fee.” Our issues are not new, Anderson implies. In these poems, the structure of recipes—lists and directives—immerses readers in the suffocating social mores of the 1950s and 60s. “So slow, the directions on how to stay newly wed,” Anderson writes in “Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air,”

marshmallow, movie, coconut, marriage, whip cream,

baby, mayonnaise, baby: the basics,

my whitewashed ranch slopped down in the canyon.

In the same poem, consumer culture forces women to become “a voice: costing time,” proving its own artificial value. Anderson contrasts cookbooks’ endless commands for women with “The Complete Cookbook for Men (1961),” a six-line poem that concludes “Are you / Listening? How much longer do you wish to cook.” Consumerism’s disproportionate burden on women comes through sharply in Anderson’s curation of sources.

Shopping receipts furnish subjects for “Receipt,” the book’s second section. Titles range from “Beauty Nails ($39.95)” to “Paid ($3,678.53 Capital One).” Here, Anderson approaches the connections between market value and family, subjects also taken up by poets Susan Briante in The Market Wonders (Ahsahta Press, 2016) and Sarah Vap in Viability (Penguin Books, 2016). All three poets ask a crucial question: Given that we can’t opt out of consumerism, how does it impact the value of the individual and our ability to be a parent? Anderson writes in “Epidural ($25.00 copay)”:

come in and scrub yourself

I am about to serve your economyan addition, which I, apparently,

shall trash, shall love. The needle the instrument of.

A distanced tone pervades Briante and Vap’s collections, driving the reader to fill the emotional gap between the information presented and its meaning. By contrast, Anderson’s tone is by turns caustic, sarcastic, and furious—sometimes rendering the speaker repellent. “I look / forward to your indoor tan, your SUV, / and your fertility kit,” the speaker of “Lacy ($292.06 modcloth.com)” hisses to a bride. But in poems such as “Clearblue Easy ($49.99 CVS),” Anderson’s tone underscores how consumerism eats away at individual dignity, a speaker’s desire to be a mother reduced to a litany of “a nurse on the phone with insurance, // with my cup and gown, my blue plus,” her value reduced to the question, “Is it covered.”

Bitterness reaches its peak in poems about climate change, primarily grouped into “Re,” Receipt’s final section. This bitterness springs from a perceived inability to effect real change, as with the DIY-crazed speaker of “Decorate”:

I know how from TV: declutter the ocean like a plastics drawer.

Stuff the poles back up with some snow;you can use the cheap stuff. Then donate.

But Anderson also hints at the rich life of the world aside from us, rhapsodizing the “Minnows of the air, swallows / and later bats, untatting the garden’s / lace of gnats and mosquitoes” (“Asparagus”). The nonhuman world also presents a drastic alternative: tearing apart present structures and starting over. Anderson concludes Receipt with the poem “Verture.” Its fragmented lines ask:

But were

I not myself—my kids,

receipts—did I not let myselfgo—my sleeves, eats,

cells—might not

I give. Might notit all unknit—a little—the kids

—less—me—less—us—now—live—

Receipt exposes the failings of contemporary American culture, failings that have been with us from the very beginning. And if that’s the case, the only way out might be to let it all go, making room for something radically different. Anderson eschews recipes for change—for her, recipes are failures anyway. Our systems, our values, and our good intentions are corrupt, Receipt argues. Anderson forces us to look at them directly, not entirely certain, but hoping that a way out exists amid the wreckage.

Published on January 6, 2017