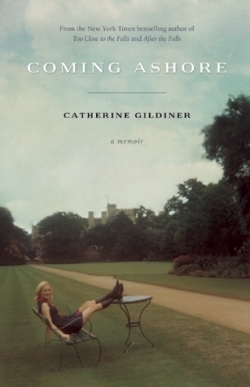

Coming Ashore

by Catherine Gildiner

reviewed by Rachel Poser

Catherine Gildiner knows how to make an entrance. She announces her arrival as a student at Oxford by sailing headlong through the glass window of the post office on her bicycle, unable to locate the “English brakes.” Readers familiar with Gildiner’s first two memoirs, Too Close to the Falls and After the Falls, which chronicle her rambunctious childhood in upstate New York, will be happy to reunite with the spirited young woman lying bloodied—yet somehow unharmed—on the mailroom floor.

Coming Ashore follows Gildiner into her twenties as she studies poetry at Oxford, teaches English in Cleveland, and starts graduate school in Toronto, where she meets her husband. Gildiner’s improbable adventures and her prose, which crackles with humor and intellect, are more than enough to delight her readers, but Coming Ashore also holds historical interest as a first-hand account of a young woman reaching maturity during the feminist awakening of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

From the very first page, Cathy McClure Gildiner seems strangely familiar. Her voice carries an echo of the beloved literary heroines who defy society’s expectations with more charm than grace—the likes of Anne Shirley, Jo March, and Elizabeth Bennett—though Gildiner’s brand of blunt sarcasm is decidedly her own. “I’d been kicked out of grade schools, arrested at age thirteen, caused a three-alarm fire—all the normal things for an American girl,” she writes, summing up her teenage years. Coming Ashore traces the dovetailing paths of personal and social change, as this “normal” American girl trips toward self-understanding in a world that learns to accept her.

Gildiner’s early escapades are some of her most entertaining. Although she is enamored with the spires and meadows of Oxford—at times beautifully described—Gildiner finds that she chafes against the false gentility of British high society. At a country estate full of debutantes and hunting dogs, she engages in a wonderfully absurd battle of wills with her friend Clive’s mother, nicknamed “Wiggles,” who “had no intention of losing her son to the colonies or to a gauche, grasping, loud Irish daughter of a tradesman.” Coming Ashore characterizes, or perhaps caricatures, the British as hopelessly class-obsessed, and Gildiner eventually decides that continued residence in England is incompatible with her up-by-the-bootstraps American values.

As the decade rolls over, Gildiner swaps her miniskirts for fringed leather vests and bell-bottoms, but she remains a magnet for trouble. Arriving in Toronto, she first cohabitates with suspected FLQ terrorists and then moves into the personal ashram of a drug kingpin named Ginger, who takes on the role of a benevolent older brother. Readers may feel these wild encounters stretch the bounds of believability, but the story is compelling enough that they may not care. “I’ve accepted that memory is not reality,” Gildiner writes in her preface. “It does not give an accurate picture of the past, for no one can do that; every memory gets shifted through our unconscious needs.”

Gildiner’s filtered past is part of the larger history of the feminist movement, a context that broadens the scope and appeal of her memoir. “Feisty women who didn’t put up with crap, the ones who came fully loaded with their own brand of testosterone, were suddenly in vogue,” she writes, describing the mood in 1970s Toronto. North America’s growing feminist consciousness provides Gildiner with the opportunity for serious reflections on life and love toward the end of the memoir, though she never loses her sense of humor: she recounts with amusement, for example, the day the women in her feminist group took turns discovering their clitorises with a magnifying mirror.

Coming Ashore is a sharp, well-crafted, and boisterous memoir that captures a young woman and a culture in transition. Gildiner is a talented storyteller with an acute sense of comic timing, and she recounts her misadventures with a lightly mocking self-awareness that makes her a compelling and likeable narrator. Readers will regret only that this memoir is her last.

Published on April 6, 2015