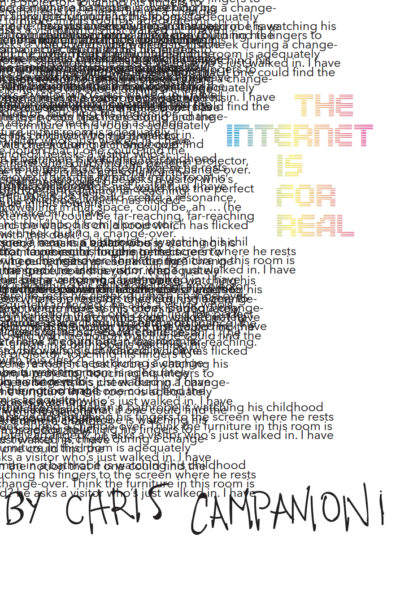

The Internet Is For Real

by Chris Campanioni

reviewed by Gabriel Garcia Ochoa

When I was twelve, my family subscribed to our first dial-up service. The Internet was not “for real” in 1996. It was a toy, something that could be turned off and forgotten while we got on with life. In the twenty-three years since, the online revolution has disrupted our cognitive processes so deeply that discussing this disruption itself has become passé. We take it for granted. Today, we no longer fetishize the Internet, but instead try to make sense of it at a practical, visceral level.

With the Internet is for real, Chris Campanioni joins a cohort of writers doing just that. Take Australian-born, New York-based Oscar Schwartz, whose poetry collection The Honeymoon Stage was written for friends made on the Internet over a five-year period. Poet Sam Riviere’s collection Kim Kardashian’s Marriage is fully marinated in electronic chatter, relating only to Kardashian in title and structure, with seventy-two poems to match the number of days Kardashian was married to basketballer Kris Humphries. There is Olivia Sudjic’s “Instagram novel” Sympathy, and Joshua Cohen’s Book of Numbers, which reads like chatspeak. Like these writers, Campanioni writes about the world where the Internet is taken for granted—but his style differs from that of his predecessors. In its five-hundred-plus pages, the Internet is for real brings together memoir, poetry, essay, and scholarly analysis. There is commentary on the refugee crisis, capitalism, privilege, and pornography; short meditations on the workings of transculturality and the Jungian interpretation of dreams; and reflections on the grotto of our collective unconscious, which now happens to be online.

Campanioni’s the Internet is for real is a threshold book. It stands at the intersection of conflicting classifications of style and genre, and refuses to take the step that would place it definitively in one camp or another. By this I do not mean that his work is half-baked, but rather that it explores potential. In his 1990 Nobel lecture, Octavio Paz explained that “between tradition and modernity, there is a bridge. When they are mutually isolated, tradition stagnates and modernity vaporizes; when in conjunction, modernity breathes life into tradition, while the latter replies with depth and gravity.” Campanioni’s work is modern, and builds the bridge Paz imagined, starting a conversation with the forms of modernity that preceded him. This is what Julia Kristeva calls “destructive genesis,” the process by which a text responds to the corpus of texts that came before it, affirming its origin while going a step further than the canon and claiming a new poetic honesty.

Three prose poems in the Internet is for real are good examples of this dialogue. “I Sit at the Broken Off,” “Proximity to the Victim,” and “Attempts to Climb” pay homage to the modernist text of Cuban letters, Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s novel Tres tristes tigres (Three Trapped Tigers). Similarly, a number of Campanioni’s pieces appear to be influenced by the Oulipo, a Francophone collective founded in the 1960s, whose members—including Georges Perec, Italo Calvino, and Raymond Queneau—use constrained writing techniques in their works. “Oulipo” is an acronym in French, standing for ouvroir de littérature potentielle, “workshop of potential literature.” It is a fit way to consider Campanioni’s writing, not only because of the techniques of constraint he adopts, but also because of his constant push for literary potential. His “Erasures” series redacts eleven pop songs, blotting out part of the lyrics (CIA-classified-document-style) until a poem emerges from the debris. “Letters from Santiago” is a series of twenty-six meditations—one for each letter of the alphabet—on dreams, Campanioni’s migrant background, and the overlaps between the two. “Manufactured Pleasures (in 72 Acts),” another constrained piece, is a collection of short autobiographical vignettes that orbit around the number seventy-two.

There are snippets of memoir throughout the book, including moving stories about Campanioni’s aging dogs, their confusion and struggle for understanding: “Amy was trying to remove herself from the manufactured life of a pet and become whatever it was she would have been. She was trying to die. And for a moment, to live.” Campanioni makes us doubt, on purpose, whether his written memories are factual or not. This is part of his ongoing commentary on our online selves, which began in his previous book Death of Art (a memoir that I also reviewed for Harvard Review). Campanioni questions how we perform our identities selectively, writing faux memoirs and presenting curated versions of ourselves.

And this raises a question we’ve been kicking around since Plato, via Borges, Baudrillard, and beyond. What is reality? Do we determine it, or just operate within it? A bit of both? That old chestnut must be cracked open if we want to understand whether art is better at home on our screens than inside a museum crawling with tourists, or if virtual reality can deliver the apex of happiness and pleasure. This is our modernity. Campanioni probes these issues with humor, depth, and kindness. There is a moral dimension to his writing, a recognition and care for the other present in the acknowledgement and love of the self. It is a writing of excess: entirely reasonable, when the subject is the Internet.

Published on November 5, 2019