Sleet: Selected Stories

by Stig Dagerman, translated by Steve Hartman

reviewed by Ross Barkan

When Stig Dagerman shuttered his garage doors and left his car engine running, he was just thirty-one. But Dagerman, who has been dead now for six decades, left behind the oeuvre of a writer twice his age: four novels, several plays, poetry, and a work of singular journalism. Remembered by bookish Scandinavians, Dagerman is lost to history abroad, unknown even to one of the recipients of the Swedish prize that bears his name. At his peak, he was likened to a Swedish Faulkner and Camus, penning searing novels while reporting from a war-ravaged Germany in his early twenties before succumbing to depression and suicide.

In Sleet, Dagerman’s most recent collection of short stories translated by Steven Hartman, melancholia threatens to derail whatever victories, large or small, are won. Knut, an alcoholic womanizer rejected by his prudish and striving family, rambles boozily through the last story in the collection, “Where’s My Icelandic Sweater?” Swearing, drinking, and failing, he gets drunk on the night before his beloved father’s funeral, fulfilling the lowest expectations of his siblings and in-laws. “And so you ask Lydia one more time,” he says of his smug sister. “‘Where’s my Icelandic sweater?’ But it’s too late. A second later and you’re out of reach, deep down under, where you don’t hear nothing and there ain’t no understanding.” Knut is a trash collector, one of Dagerman’s many downtrodden protagonists, portrayed here in an unadorned, naturalist style that is a departure from some of the writer’s other works.

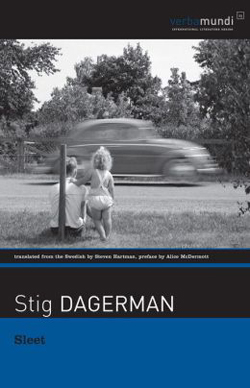

In the delicately brutal story “The Stockholm Car,” a group of farm boys watch as a luxurious automobile from the city rumbles through their backwoods and scratches the horn of a heifer. Rather than castigate the boys, the rich driver and his pretty daughter simply ignore them: “What terrifies us most of all,” the narrator recalls, is that the Stockholmer, “won’t even acknowledge us, that somehow we don’t really exist.” Their fears are confirmed when the car speeds away and the farm boys are left with “all our longing and shame.”

Even though World War Two is never mentioned, its shadow is inescapable in these stories. Dagerman did not see combat but he reported on the plight of the German civilians who, in the wake of the Allies’ victory, were left with their own ruins and without the spoils of war. Empathy for everyone caught between history’s bloody teeth pervades his work. The most familiar motif of war-scarred fiction, that of innocence lost, threads Dagerman’s cinematic scenes, emerging most viscerally in “In Grandmother’s House.”

In this story, a boy living in the country with his grandparents confronts the overwhelming silence of his house. When his grandmother explains that no true silence exists, he tries to hear the silence the way she does, but fails, instead making up sounds to distract her. Finally, he tells her he hears soldiers. “‘Soldiers,” he had said triumphantly. Because in that moment he knew why she was shaking. She was afraid. She was afraid because she couldn’t hear what he heard.” Redemption is ultimately found, but the message in Dagerman’s uneasy universe is clear enough: in the gaps that lie between understanding, the evil still lurks.

Critics often find fault with Dagerman’s earnestness. There’s an overwrought, lugubrious quality to some of his writing: children cry, mothers keen, and the maudlin set pieces—drunken fathers, provincial townspeople—stay in full rotation. But even here, Dagerman is more than redeemable. As he shows in a story about a dispirited boy named Håkan, who grows into a downtrodden, adolescent mailman, a child’s despair is always poignant. That outsized and world-devouring fear you can know when you’re young, Dagermans suggests, is no less relevant when time has erected a buffer between it and adulthood. Perspective, whatever that truly means, does not dull pain.

To the more than sixty million slaughtered on all sides of the war, blood was blood and death was death. A German mother, Dagerman understood, could grieve as desperately as a British mother. Your sadness is yours—geopolitical whims, bank accounts or dates of birth be damned.

Published on August 19, 2014