Cultural Studies

by Kevin A. González

reviewed by Andrew DuBois

It is a paradox of language that as a word gains more traction, its meaning grows more slippery. The word “culture” is just such a case: laid on too thick or spread too thin, it morphs from airy abstraction into battering ram and back in the blink of an eye. In his volume of poems called Cultural Studies, Kevin González uses the word in its adjectival form in title after title: “Cultural Stud,” “Cultural Slut,” “Cultural Sellout,” “Cultural Spar,” “Cultural Strumpet,” “Cultural Scheme,” “Cultural Shock,” “Cultural Schmooze,” “Cultural Soliloquy,” “Cultural Scope.” The result is both a comic critique of a repetition compulsion and an ambivalent admission of the term’s loose utility.

A native of Puerto Rico, González shows us how foundational that island and its culture are to him and his poems, as he reminisces about his youth (in one poem he movingly apostrophizes “Youth” itself) and tells stories about returning home after sojourns in Pittsburgh, Iowa, and Wisconsin. The poems prove that being peripatetic does not preclude being anchored: “Always, there has been a backpack / strapped to your heart, & asking Where are you from? / has not been unlike asking, What is this poem about?”

In addition to the many place names and the occasional easy shifting from English to Spanish, there is a sense of movement in the way González switches between the first and second person. Though the book begins with “I,” it is “you” that predominates, as if some detachment is necessary to understand oneself in a life marked by dislocations. This grammatical device draws the reader into González’s well-told stories, since we can’t help but hear ourselves addressed (“Hey, you!”). To the poet’s credit, he gives us over half the book to figure this out for ourselves, after which he admits to being self-conscious about hiding behind the deflecting pronoun: “it’s Halloween, & you’re disguised / in the second person”; “All I really want / is to be You for another twenty seconds / & maybe pull this off.”

As these lines suggest, there is an underlying sense here that poetry is an elaborate form of lying, a con that one “pulls off” by being “disguised,” or by overemphasizing the “cultural” because it is a hot poetic commodity. This comes through not only in subtle hints from the poet’s father (who, himself capable of dissimulation, appears in several poems where he is wary of being represented), but also in the remarks of a fellow poet, who tells González “to be thankful / because at least you have a shtick.” But the poet is so determined to reveal his methods—just another part of the con?—that he lets us in time and again to the institutional context of his craft:

Back when I still believed in God

is not a good way to start a poem

& perhaps that is why Iowa passed

& you wound up in an MFA Program

full of vegetarians who say

your poems are all about sex or poets

or having sex with poets

or not getting into Iowa.

Although we know that hardly any young poet gets published these days without the workshop imprimatur, it is annoying to have the facts pushed in our face, as if the poet is pulling back a curtain or breaking a spell. The annoyance passes when one realizes that this is actually a starker form of realism than is usually encountered in books of poems, risky in its resistance to our fantasies of the untutored poet. (No worries, though, González got into Iowa after all.)

By the end of Cultural Studies, the “I” and the “you” at last share the page with a “Kevin A. González.” In between these formal poems (matched elsewhere in the volume by two strong sestinas) is a suite of free verse couplets, impressionistic responses to three fights by the Puerto Rican legend Félix Trinidad, a ferocious boxer who won belts in three weight classes. The poet thus enters an august tradition, for the connection between pugilism and poetry goes back to Homer and has never since stopped yielding verse. Having read that González attended at least one of the eponymous fights (“The Night Tito Trinidad KO’ed Ricardo Mayorga”), this fight fan wished at first for a more ringside, sports-writerly approach. But the rightness of his response must be conceded. Ring Magazine and YouTube clips can convey the facts of the fight just fine. But only González can convey what Felix Trinidad might mean to a fellow native son:

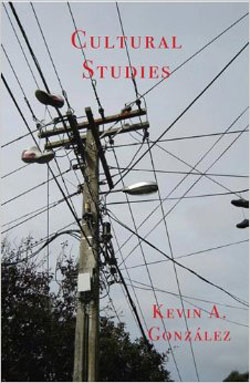

Our culture is a pair of Adidas

dangling from telephone lines& a small child reaching up,

fists gripping air,arms brief and contained

like the two o’s of colony.

Published on March 6, 2015