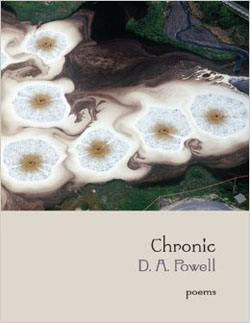

Chronic

by D. A. Powell

reviewed by William Doreski

This is D. A. Powell’s most varied collection. His three previous books—Tea, Lunch, Cocktails—were as concentrated as their menu-titles suggest. Chronic refers not only to a social and personal condition but jauntily abbreviates “chronicle.” By conflating a public or private disorder with a perceptive recounting of the everyday, Powell depicts a world in which the comforts of pop culture (“meditating upon the meaning of the line ‘clams on the halfshell and rollerskates’ in the song good times by chic”) coexist comfortably with vicious aberrations (“the confidence man”). Powell offers an array not only of wildly varied subject matter but of verse forms ranging from the relatively compact lines of “clutch and pumps”:

if I were in your shoes, you purse your mouth

but you were never in my shoes, chinaberry

nor I in yours: the cherry ash of fags

burns your path down the scatty streetsto the lanky undulations of “corydon & alexis”:

shepherdboy? not the most salient image for contemporary readers

nor most available. unless you’re thinking brokeback mountain:

a preference already escaping. I did love a Montana man, though no good

shepherd . . .

Powell deftly avoids the boggy places into which such apparently casual line-making can sink, and creates an elaborate catalogue of effects available to contemporary free verse. The overall effect suggests great control but maintains a firm grip on the casual.

Like many other contemporary poets, Powell instinctively grasps at metonymy not merely as a local effect but as a structural device. A lyric alternative to the expository rhetoric common to orderly structures like the sonnet, or the narrative devices of the monologue, metonymy seems to reflect reflection itself. Mimicking the movement of the mind, it trips the poem along a path that could otherwise be plotted only by the immense mathematics of topology. In a poem like “shut the fuck up and drink your gin and tonic” (most amusingly footnoted as “Apathy at Harvard, 2001–2004”), the movement from one motif to the next occurs with rhetorical flourish. While Powell shapes his lines to suggest the most indolent approach to composition, he revels in exposing both his segues and aporia:

send down the little nibblies, will you barkeep: the ones called stupor

and deficit and “well anyway, the cockroaches will survive.” oh you kids:

still that awkward growth spurt that started when you were sperm

The interpolation of colloquial clichés, odd punctuation, lack of capitalization, parentheticals, and unattributable quotations characterize Powell’s aesthetic.

In the title poem, the speaker remarks, “here is another in my long list of asides,” and so we might be tempted to see Powell’s poems primarily as lists of asides, which many of them are. This humorously casual poetics produces many engaging and witty poems, but in the section entitled “Terminal C,” some of the poems darken into a seriousness not only of subject matter—serious illness—but of more intense focus and a simplification of poetics to accommodate harsh and crisp metaphors, as in, “when the nightnurse appears in your doorway / she’s a raptor outlined by the last good light,” from “hepatitis ABC.”

And so the entirety of “cancer inside a little sea,” which with its triply punning title (all the c’s, whether of cancer or in titles, are lower case) depicts a landscape of efflorescence, scum and crud, creeping vines, and contaminated mud. The question the poem asks is the familiar ecological poser: “child to come, what will you make of this scratched paradise,” but the means of achieving this interrogation draws upon A. R. Ammons’ plenitude channeled through Powell’s vision of a culture-creep-depleted natural world.

This depletion, almost a vision of entropy, empowers “republic,” one of the most comprehensive of Powell’s poems. It depicts an agrarian world compromised and then crushed by industrialization. The poem notes that through this process the very language of agriculture gradually has become debased in the public vocabulary, though retaining some flavor:

it meant something—in spite of machinery—

to say the country, to say apple season

though what it meant was a kind of nose-thumbing

and a kind of sweetness

as when one says how quaint

knowing that a refined listener understands the doubleness

The poem closes, however, not with an encomium on the state of food production and planetary exhaustion but with a moment of awakening into the essentially fictional fact of writing:

meanwhile, where have I put the notebook on which I was scribbling

it began like:

“the smell of droppings and that narrow country road . . . ”

Powell refreshes the notion of open poetry by refining the line and recharging the metonymic imagination with a culturally adaptive energy. Chronic is funny, a little cruel at times, and filled with readable, amusing poems like “clown burial in winter” (“meringue icing beaten over hot water, ruffle-edged”) and “chrysanthemum” (“wherever he wakes this morning, he knows the big bang is irreparable”). Reading through it constitutes a tour—a chronicle—of America as perceived by a chronic loser of love and identity, a voice prone to cultural and psychic drift of a highly productive kind.

Published on March 6, 2015